Dear Global Intelligence Letter subscriber,

The road from Bandung to Sukabumi, on the Indonesian island of Java, winds through some of the most picturesque tea plantations I’ve ever seen. The rows of tea plants cascade like a rich, green quilt down the hills, jump across the winding, two-lane road, and continue rolling toward the valley in hypnotic symmetry.

It’s inspiring scenery. A photographer’s dream.

Not that my colleague was paying attention to any of that.

Hours earlier, we’d left a food court at a nice shopping mall in Bandung, where she’d drank too much water with her curry. We were now nearly five hours into a trip that was supposed to last less than three—and we were still hours from our destination.

It turns out the growth of the Indonesian economy over the last couple of decades has handed a car, motorcycle, or scooter to every Indonesian with a pulse—and every last one of them seemed to be on this particular stretch of traffic-choked highway. Worse for my colleague was that we were in the middle of nowhere—tea plantations stretching for miles in every hilly direction.

There was, in short, no place to dispatch with the excess of lunchtime liquids that had settled in her bladder. Stopping on the side of the road was a no-go. Frankly, there was no “side of the road”—just a tumble down the hill into those rows of never-ending tea plants.

She looked at me, on the verge of tears. I tried to communicate as best I could with our Indonesian driver. He understood, but shrugged. “Really—where to stop?”

Minutes later, however, the driver found a pull-off near a small village. He pointed to the toilets—wooden sheds with holes cut into a wooden bench, sitting atop a hole in the ground. The stench…mmm, I leave that to your imagination.

My colleague nearly lost her mind.

I shrugged.

“It’s your only option,” I offered.

“No!” she shot back. “I can’t. I did the math: I have enough antibiotics back at the hotel to deal with a urinary tract infection until we’re back in the States.”

“Don’t be stupid,” I pressed. “It’s just a hole in the ground. I’m sure you’ll be fine…probably. Just beware of splinters.”

She looked angry.

Just then, a wrinkled octogenarian approached. He looked at my colleague, pointed to a nearby set of stairs up a hillside, and said in his best broken English: “KFC. Up. Toilets—nice.”

My colleague, now crying, slapped my shoulder hard and exclaimed: “See!? He doesn’t even know me and he loves me! You don’t love me!”

I tell you this tale of a traveling, toilet mishap because it touches on a truth near and dear to my heart as an investor: the rise of the middle class outside the West.

In the center of rural Indonesia, in the middle of a vast, emerald sea of tea that seemed without end, there sat a KFC—one of the most iconic consumer brands on the planet. That fact says so much about the level of opportunity in emerging-market economies.

I’ve been bullish on emerging markets for nearly 30 years now. They’ve had their ups and downs, like all asset classes. Now, however, after nearly a decade of down, emerging markets are on the cusp of a strong period of up.

Fueling their imminent rise are the after-effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. For those after-effects are about to unleash a trend the world has seen only three times in the past 125 years: a commodity super-cycle.

And where there’s a commodity super-cycle, there are emerging-market economies, like Indonesia, on the verge of a boom.

Therein lies our profit opportunity and it’s a big one, given that we’re moving into just the fourth super-cycle in more than a century.

In many ways, this month’s cover story follows on from the March and April cover stories on the weak dollar and rising inflation. Those two factors combined play a central role in the commodity super-cycle to come and the impact that this will have on emerging-market economies.

I’ve been following the emerging markets for nearly 30 years now. In fact, they’re the reason I began opening brokerage accounts all over the world in the 1990s and early 2000s.

At one point, I was buying stocks directly on exchanges from New Zealand to Zambia, Malaysia, Egypt, and Romania. I was doing so because I realized what we in the West once pejoratively called the “Third World” was rapidly emerging as an engine of consumer growth.

What were once poverty-ridden backwaters of hopelessness and shoddy manufacturing are now the most dynamic economies on the planet.

Today, the roughly 25 main emerging markets account for nearly 22% of the world’s population, but 60% of global economic growth and nearly 50% of its total economic output. The stock markets of these countries combined are worth more than $20 trillion (the size of the U.S. economy, by comparison) and they’re home to more than 18,000 listed companies.

I saw all of this for myself as an investor traveling the world to write about global investment opportunities emerging from the rise of the non-Western middle class. (I even wrote a book about this: Replay: Your Second Chance to Invest in the American Dream.)

I visited soybean farms in Uruguay; a hyper-mart in Barranquilla, Colombia; a Ferrari dealership in Warsaw, Poland; and banks in Russia, Singapore, Turkey, and Kazakhstan.

I saw the processing of raw cocoa beans and a high-end boutique selling Western-style wedding dresses in Accra, Ghana; I traveled through Myanmar, Cambodia, and China…through northern Romania, southern Nicaragua, eastern Kenya, and western Java (where my colleague’s toilet trauma transpired).

What I can tell you after more than 100,000 miles of air travel is that much of the wealth that these billion-plus new consumers are spending is a direct result of commodities—the raw materials like copper, wheat, sugar, and natural gas that go into everything from iPhones to Ford F150 pickup trucks to so many packaged food products (and the packages they come in) that we buy on our weekly pilgrimage to Piggly Wiggly.

The rolling tea plantations on the Indonesian island of Java.

See, our world is divided between makers and takers. That’s true of people as well as economies.

We in the West are takers—have been for decades. Sure, we make stuff, but our economies today are primarily dependent on consumerism—buying (taking) what other countries make.

And what those maker economies make are commodities. They’re mining, growing, harvesting, and refining all those raw materials that go into making the products we buy.

Because of that, emerging markets are almost exclusively commodity economies…meaning that they ebb and flow with commodity prices.

In the decade between 2000 and 2009—during the last commodity super-cycle—emerging markets and/or commodities were among the top two investment asset classes in eight of those 10 years.

For the last decade or so, however, they’ve been ebbing for two main reasons:

Now, however, we are on the cusp of a paradigm shift. We’re about to see the script flip.

The strong dollar/weak commodity environment of the last decade is already turning into a weak dollar/strong commodity environment.

The result of that will see the emerging markets rally. That’s what we want to be a part of. That’s the trend that is going to propel this month’s investment recommendation.

What makes me confident this script flip is imminent are three fundamental truths about emerging markets. They thrive when:

This is an emerging-market trifecta, and it’s going to lead us to…

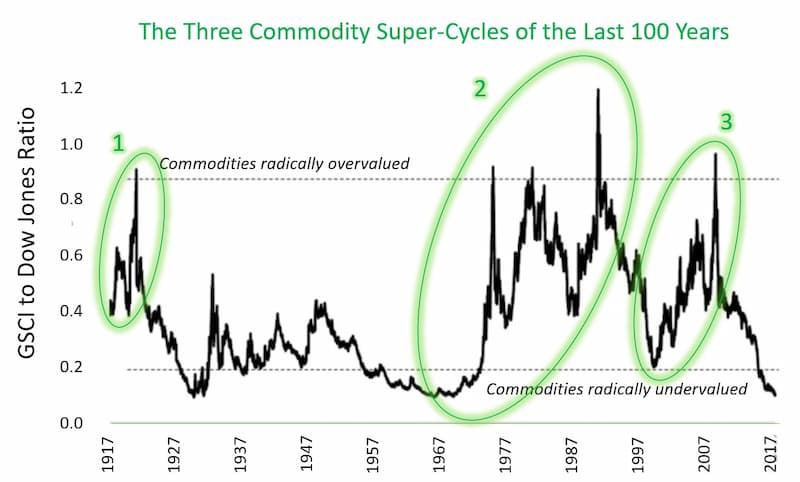

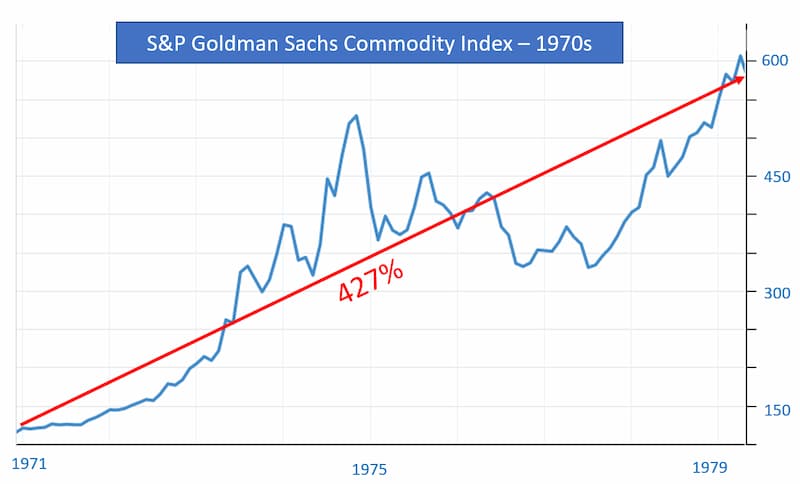

On three occasions over the last century, commodities have launched into a so-called super-cycle—a period that lasts a decade or longer and which sees commodity prices shoot the moon.

You can see those three super-cycles in this chart of the S&P Goldman Sachs Commodity Index between 1917 and 2017.

Each of those super-cycles was caused by a major event.

Number 1 occurred amid the rapid industrialization of the U.S. in the late-19th and early-20th centuries.

Number 2 sprang from the emergence of the Western European and Japanese middle classes, a process that didn’t really begin until Europe and Japan had fully rebuilt in the decades following World War II.

And Number 3—the most recent—was caused by the rise of the so-called BRIC nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China) as they began their climb out of poverty.

The Global Financial Crisis in 2007-2008 killed that third cycle prematurely; since then, commodity prices have fallen farther and farther, to the point that this is where we are today…

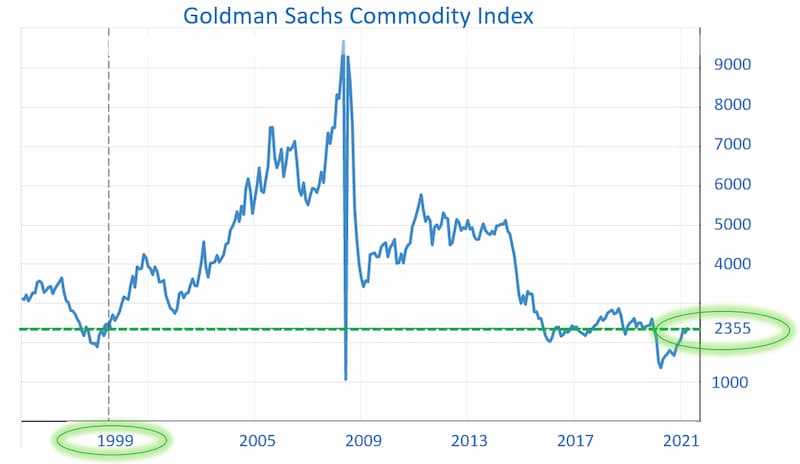

At present, commodity prices are on par with the summer of 1999.

That, in part, goes a long way toward explaining why inflation has barely touched your wallet in the past decade. Goods have been very cheap to produce, because the prices of raw materials have been so very low.

In short, the past decade has been horrendous for commodities.

Now, they’ve bottomed out and we’re about to begin a new super-cycle. This one, however, will be slightly different.

See, those last three super-cycles were all driven by a fundamental, societal change—the rise of middle-class economies in the U.S., Europe/Japan, and the major emerging markets.

This time, the driver is financial, not societal.

For the most part, the emerging markets have emerged. Heck, China, the most important emerging market, is increasingly a consumer economy, just like the West.

True, there are many other emerging markets still pursuing that goal, but they’re smaller and their combined financial weight isn’t enough alone to send commodity prices racing moonward again for a decade or longer.

What is weighty enough, however, is money.

Lots and lots—and lots and lots—of money.

Prior to the pandemic, debt was already a problem in the world.

Frankly, it was a problem in the world back before the Great Recession. But instead of using that crisis as a motivation for fixing a debt-addled global economy, governments, consumers, and corporations have used the last 13 or so years to simply pile on more and more debt.

Back in 2007, before the Great Recession attacked, global public debt was about $142 trillion, roughly 245% larger than the global economy. That’s not good.

Today, global debt is $282 trillion, or about 325% of the global economy.

That’s a level of insanity without any sensible analogy.

But no one cares. COVID-19 changed the mindset globally.

Before the pandemic, politicians at least mouthed some kind of (faux) angst about debt. Post-pandemic…well, it’s like COVID erased any pretense of caring about debt.

U.S. politicians have dumped some $6 trillion into the economy over the last year, while European counterparts have spent similarly. All of that spending comes from borrowing.

And all the borrowing is important to our story because vast money printing leads to a weakening dollar and rising inflation.

Let’s go to another chart:

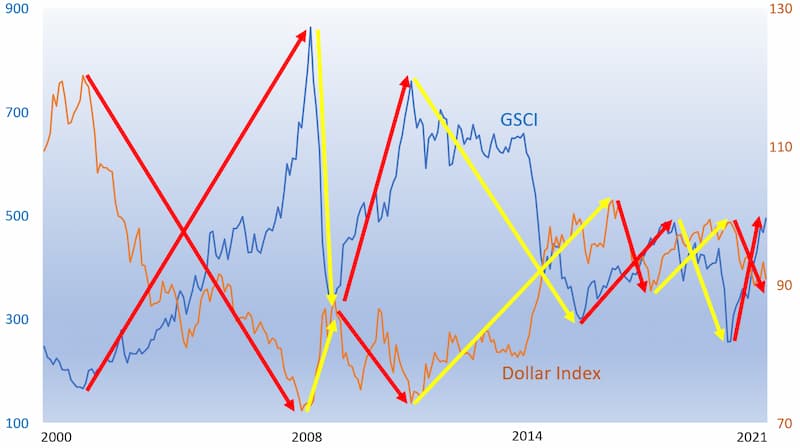

The orange line is the U.S. Dollar Index, which tracks our greenback against a basket of world currencies. The blue line is the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index, or GSCI, which tracks a basket of commodities that span everything from wheat, soy, and cattle to oil, gas, and various industrial and precious metals.

I’ve annotated this with colored lines to show you one of the clearest trends in the financial markets: commodity prices and the dollar move inversely.

The yellow lines show you that when the dollar is gaining strength, commodity prices are falling. The red lines show you that as the dollar weakens, commodity prices are rising. You can see in this chart that almost 100% of the time the dollar/commodity trend holds fast.

Below, I’ve expanded the last section of the chart. It shows that the strong dollar/weak commodity environment of the last decade is already turning into a weak dollar/strong commodity environment.

The reasons for this trend are actually pretty simple:

We can apply that bit of knowledge to look into the future with a great deal of certainty…

The U.S. dollar, as I explained in the March issue, is moving into a period of weakness, driven by the huge and rapid increase in government debt. Uncle Sam’s debt is now at $28.2 trillion, or 130% of total annual economic output. There’s more to come since governmental overspending remains a primary tool for budget planning in the U.S.

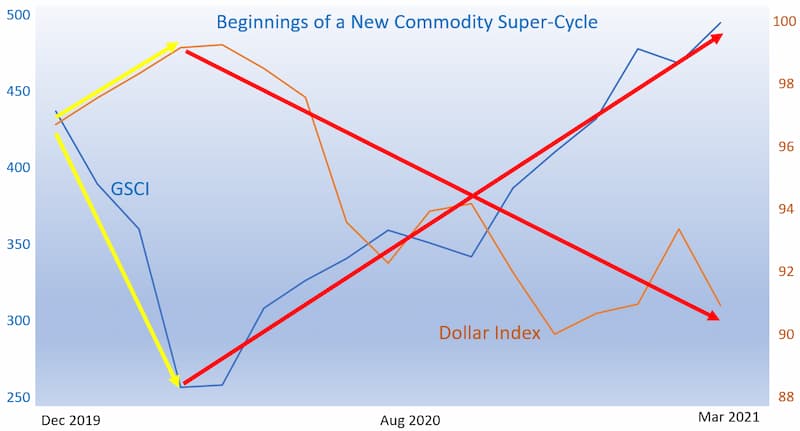

America's fiscal situation is clearly weighing on the dollar already, which you can plainly see here…

For an all-too-brief moment, the dollar rose strongly in value against other currencies in the early days of the COVID crisis (the yellow box). That was the global investors seeking a safe haven in the dollar amid so much social and economic uncertainty.

A year on, COVID is a known quantity, and investors are worried about the impact that so much additional—and increasing—debt will have on the world’s most important currency, the dollar. And so, the value of the dollar has fallen sharply.

Expectations of a long-term weak dollar are now popping up all over the place. A recent Reuters survey of global investment strategists found that half of them expect a weak downward trend to last one year or longer (“longer” being more than two years).

We know from our charts that when the dollar sinks, commodity prices rise.

So, we have that bolstering emerging markets.

And then we have inflation.

Just like with those weak-dollar expectations, so, too, are inflation expectations rising. From Singapore to India, the U.K. to Australia, inflation concerns are bubbling up globally.

In Ekaterinburg, Russia, last month, my wife and I went strolling through a typical, low-end Russian supermarket hunting a Red Bull. My wife (she’s Russian) overheard two babushkas complaining that cooking oil prices “are just stupid! Do they think we live like royalty?”

Back at the hotel, I checked Russian inflation and saw that the March reading, the latest, had just come in at 5.8% on an annualized basis. A four-year high and well above expectations.

Similarly in the U.S., inflation hit a 10-year high at the producer level—meaning prices producers pay for the raw materials (the commodities!) they need to build their products.

Consumer-price inflation in America, meanwhile, recently advanced at a pace not seen in nine years. I’m quite certain you’re already feeling it in your own wallet.

Prices for a pound of bacon are up more than 8% in the past year, according to data-analytics firm NielsenIQ. Ground beef is up nearly 5%. Bread, 9%.

Overall, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which tracks inflation, says food prices are up 3.9%, and the Department of Agriculture says to expect another 3% rise this year. (You can bet those numbers are adjusted to appear lower than reality.)

In the April issue, I laid out the case for inflation to hit 4% or 5% this year. That’s a big number, no different than throwing away 5% of every paycheck.

Well, just recently Neel Kashkari, president of the Minneapolis branch of the Federal Reserve, said he wouldn’t panic if inflation heats up to a 4% annual rate.

That comment tells you so much!

It says that even the Fed now sees that wallet-draining inflation is in the offing, and it’s trying to control the message before consumers feel the impact and start to worry.

This is another sign for us that emerging-market economies are soon to see a boost.

When inflation takes off, investors race to own “hard assets”—gold, bushels of wheat, barrels of oil, etc. That’s because inflation pushes those prices higher, so investors want to own assets going up in value.

Conversely, inflation tends to be a drag on “paper assets” like the dollar, stocks, and bonds. I’ll use stocks as my “for instance.”

Because inflation pushes up raw material prices, companies have to pay more to make their products. Those added costs eat into profits. As profits weaken, stock prices weaken. We saw that across the 1970s.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average had a heck of a run in the post-war years—up more than 400% between 1950 and 1966, when the Dow peaked at just under 1,000. Not coincidentally, that was right as inflation started to perk up.

By 1974, when inflation was running at double digits, the Dow had sunk below 600. It wouldn’t see 1,000 again until the so-called Super Bull market began in 1982. I expect that the rest of the 2020s are going to look a lot like the 1970s…like this:

During that same decade, the 1970s, commodities did this…

Seems pretty clear: In an era when the dollar is weakening and inflation is rising, the place to have your money invested is in commodities…which means the place to invest is in the commodity-driven emerging-market economies.

But we’re not done yet…

There’s another unique reason commodities have the wind at their back: pent-up global consumer demand and excessive government spending, both stemming from the pandemic.

All those economies that shut down, all the businesses that had to shutter, billions of consumers who couldn’t spend as they normally do—there’s a lot of money waiting to be used. Indeed, the savings rate in the U.S., Japan, the U.K., and elsewhere in Europe shot up above 20% from the low- to mid-single-digit range.

As the global economy reopens over the remainder of 2021 and into 2022, consumers are going to pour those savings into a spending binge. And all the stuff they buy starts off as a collection of commodities.

As for governments, they’re taking the exact opposite approach to the one they pursued during the Great Recession and the resulting debt crisis in Europe.

Back then, “austerity” was the mantra of the day. Now, “stimulus” is the buzzword. The U.S., as I noted earlier, has spent roughly $6 trillion on stimulus in the past year, much of it going directly into the pockets of consumers. On top of that, the Biden administration is looking to spend $1.8 trillion on infrastructure.

The European Union, meanwhile, has spent almost equal to the U.S., and now it has laid out a plan to pump roughly $725 billion into “green tech,” part of a stimulus effort to fight climate change.

Those infrastructure spending plans in the U.S. and the EU are going to demand honking big hunks of industrial metals and other commodities.

And even as the U.S. and Europe spend monstrous sums of money, there’s another place spending massively, too, though U.S. investors aren’t really paying much attention to it. I’m talking about China and…

Twenty years ago, BRICs were the trend. Everyone wanted to own exposure to the four, big emerging economies—Brazil, Russia, India, China.

China, of course, was the main member in that quartet, and the phrase of the day was “I want to own whatever China is buying.”

The idea was that if China needed iron ore to build out its economy, you went to Australia and owned the ore miners. If China needed soy to feed its citizens and grow its strategic pork reserve (yes, that’s a thing; pork is seriously important in the Chinese diet), you went to the U.S. and Brazil to own the giant, soy agro-businesses.

Well, today, China has emerged—it’s an economic behemoth. Increasingly, it is looking outward to solidify its connection to the resources it needs for an exploding consumer economy, as well as the trade ties it needs to keep hundreds of millions of Chinese workers employed.

As such, the new phrase today should be: “I want to invest where China is investing.”

And where China is investing is along the old Silk Road, the fabled paths and seaways that connected ancient China to the Middle East, East Africa, and Europe.

China is remaking that Silk Road under a new banner: One Belt One Road, or OBOR. Its aim is to spend heavily—upward of $8 trillion—on infrastructure to physically bind it to Central Asia, Europe, and Africa through new roads, rails, and ports.

A big part of what China wants from OBOR: secure access to commodities. Which means… If we invest where China is investing, we are investing in commodity countries that will benefit broadly from the commodity super-cycle soon to unfold.

This is a relatively new exchange-traded fund; it has been around since the fall of 2017. During that time, it has largely treaded water. But in the past year—as global trade rebounded from the pandemic and the new commodity super-cycle started to emerge—the fund has nearly doubled in price.

Normally, I’d pass on the chance to put my money into an investment that has already nearly doubled in short order, but this is a unique moment.

The bulk of the return over the past year has simply been a rebound from the knee-jerk collapse that happened in the immediate wake of COVID’s emergence in the West in January through March of last year. Measured from its pre-collapse price, the fund is up only about 11% as I write this in late April. It has much farther to run as the commodity super-cycle plays out.

The fund’s aim is to basically follow China by investing in countries that are benefiting, or likely will benefit, from China’s massive spending on its OBOR initiative, which is also known as The Belt and Road Initiative. That means places like Russia, Malaysia, Poland, South Africa, Indonesia, Thailand, Turkey, and others. All of those are emerging-market commodity countries.

The fund holds about 130 investments as of April, 78% of which fall into the industrials, materials, and energy sectors—i.e., commodities.

That gives us deep and broad exposure to everything from pulp and paper, to aluminum, gold, natural gas, platinum, nickel, and iron ore. All of those play into consumer demand globally, as well as the ramped-up infrastructure spending that will happen in the U.S., Europe, and China.

A couple of examples of what the fund owns:

This is what the top-10 holdings look like, where the companies are based, and the industries in which they operate.

These are the types of companies we want exposure to as the commodity super-cycle plays out. We want a broad swath of commodities across a broad swath of emerging markets. That’s because not all commodities will move equally.

Some will soar. Some will meander. Some might go lower for one reason or another. By owning a fund like OBOR, we have the field covered with commodities that benefit from pretty much every facet of life: agriculture to industrial processes to consumer products to infrastructure construction.

OBOR trades on the New York Stock Exchange, so you should have no problem buying it through any brokerage account.

The fund wasn’t around for the last commodity super-cycle, so there’s no analog to compare it against.

However, the Templeton Emerging Markets fund was active during that period, and it’s share price quadrupled between 2001 and 2007, just before the Great Recession derailed the commodities bull market. Annual distributions—basically dividends and capital gains that the fund receives from selling stocks for a profit—also soared.

I won’t say that OBOR will quadruple. But I do expect we will see the ETF double in price over the next few years. And I expect we will see our annual distributions rise markedly.

The last distribution arrived in late December and was $0.55 per share, which at that time represented an annual yield of about 2%. The next will certainly be larger.

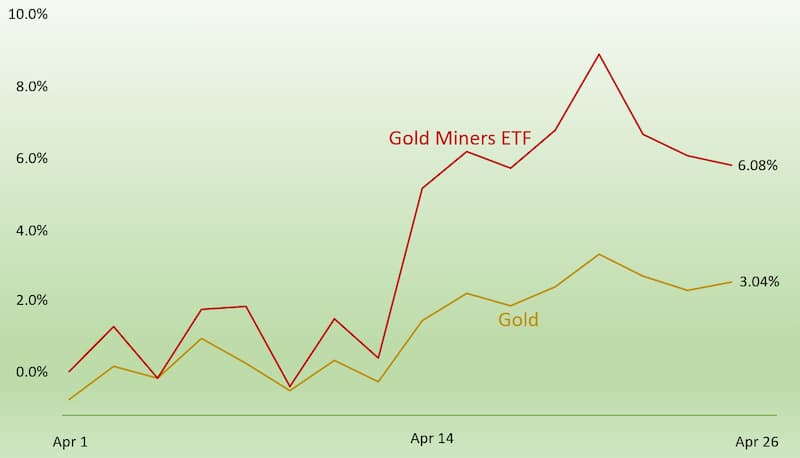

April was a fairly good month for gold, which means it was a fairly good month for our position in iShares MSCI Global Gold Miners ETF.

At $1,781 per ounce as I write this, gold prices are up $100 per ounce, or about 6% in April. Our gold miners ETF, however, is up about 10% in the same period. That reflects one of the primary reasons we want to own the miners: leverage.

If you own one ounce of gold, you benefit only from the rise in the per-ounce value. But if you’re a miner, you own millions of ounces in the ground. So, every dollar’s worth of increase in the price of gold spreads across all those ounces of gold you produce. And because miners have a largely fixed-cost structure, all those new ounces they mine generate revenue that pretty much falls directly to the bottom line.

If, for instance, you mine 1,000 ounces of gold at $1,500, you’ve got revenue of $1.5 million. But if you mine the next 1,000 ounces at $2,000, you’ve got $2 million in revenue spread across the same cost structure. Effectively, it’s windfall profits.

Wall Street obviously recognizes this, so gold-mining stocks tend to outperform the raw metal. (To be clear, though, I think everyone should personally hold some amount of physical gold in a safe place at home or in a safe-deposit box. It’s financial insurance, just in case an economic, monetary, fiscal, or social crisis erupts and undermines the dollar.)

Our gold miners ETF outperformed gold in April.

Overall, our position in the Global Gold Miners ETF is up about 14.5% since my recommendation back in March. At just under $30, the ETF remains a couple bucks away from my $32 buy limit. So, if you want to build a position in gold miners, you still have a little wiggle room to do so.

Our position in the Norwegian krone, the currency of Norway, was up a bit more than 2% in April, a nice move for a currency.

A British publication noted that the krone is “the diamond in Europe’s rough.” It pointed out that the currency “could accelerate through 2021…as Europe frees itself from a coronavirus vaccination mire, a global economic upswing lifts oil prices, and the Norges Bank (Norway’s central bank) raises interest rates before any of its peers.”

In raising interest rates, the krone would attract investors looking to collect higher interest payments on their cash. That demand would push the krone even higher relative to the U.S. dollar, which is burdened by the Federal Reserve’s adherence to a zero-interest rate policy these days.

Overall, we’re up about 4% in the krone, and I expect it will move higher from here, given the fundamentally positive tailwinds blowing on the krone. I don’t have a buy-up-to price on the krone—just buy it when you can. Currencies generally move relatively slowly so you don’t need to FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) into it.

I’m adding to the krone periodically through my bank account here in Prague, which allows me to hold multiple currencies in one account.

The easiest way to own the krone in the U.S. is through TransferWise, now known simply as Wise. You can convert dollars to krone directly in the smartphone app or on the Wise website, and simply let the currency sit in your online wallet. (I do not benefit in any way from telling you to use Wise. I am simply sharing with you a service I personally use and that I know to be reputable.)

Yara International, our Norwegian fertilizer Company, is up about 3% this month. The company recently announced it will pay its annual dividend on May 26 to investors who own the American depositary receipts (ADRs, or basically the shares) as of May 10.

The dividend is 20 Norwegian krone per share (about $2.41), an increase from the 18 krone a year ago. Because each ADR represents half of a Yara share in its home market of Oslo, you can expect to receive 10 krone per ADR, or about $1.20 per share.

Based on our buy price of $26.13, that’s a very solid annual yield of 4.6%. You can expect to see that cash in your portfolio in late May. And if you don’t own Yara, it remains a buy up to $30.

As for our position in Invesco CurrencyShares Swiss Franc Trust, it’s flat. But it remains a position you should add to when you can.

The Swiss franc consistently strengthens against the dollar over time, and all the ingredients are in place for the dollar to weaken going forward. The franc will rise in value relative to the buck.

By Kim Iskyan

Kim Iskyan is an expert on international markets who worked in emerging economies for nearly three decades, has advised Fortune 50 companies on political risk, and has helped build stock exchanges from scratch in countries that few people could find on a map.

The world is running out of energy.

Global electricity demand is expected to double over the next 30 years, as people in emerging economies acquire rich-country toys and habits.

Today, the average person in China uses a bit more than one-third of the electricity of someone in the U.S. The average Indian, meanwhile, consumes just one-tenth the electricity of an American.

As these massive economies (and other emerging markets) develop, they’re going to demand more and more energy. The question facing governments is how to provide this electricity without destroying the planet.

Nineteen of the 20 hottest years in recorded history have taken place over the past two decades. Last year, temperatures in the Arctic Circle topped 100 F. Science says that carbon-producing fossil fuels are largely to blame.

Any hope humankind has of achieving “net zero”—carbon neutrality, whereby no new emissions are added to the atmosphere—is contingent on clean energy.

The only other options are that the lights stop working. Or that we continue the steady degradation of the Earth, with our children paying the price.

In other words, to save the planet while meeting its energy needs, the world will have to turn to a dependable, carbon-neutral power source.

The world will need uranium.

Uranium has long been the red-headed stepchild of energy. The mere mention of its name provokes thoughts of atomic weapons and international conflicts.

But the element is also the basic building block of nuclear power. Processed and enriched uranium is used as fuel for nuclear reactors. And unlike fossil fuels—which deliver more than three-quarters of the world’s energy—nuclear energy is completely carbon-free.

In the U.S., nuclear power currently provides about 20% of all electricity. In Belgium, France, and Sweden, it delivers more than one-third.

Overall, nuclear power accounts for around 10% of the world’s electricity…about twice the combined contribution of solar and wind, according to the World Economic Forum.

Critically, nuclear energy also provides what’s called “baseload” power. Wind turbines need wind and solar panels require sunshine. But nuclear power plants aren’t dependent on anything but uranium—and that means they are reliable.

A stable electricity grid needs power sources that supplement each other, so even in a world that embraces renewables like solar and wind, nuclear power is expected to play a key role.

Many prominent environmental advocates acknowledge this. In 2018, Microsoft founder Bill Gates, a noted climate change evangelist, said, “Nuclear is ideal for dealing with climate change, because it is the only carbon-free, scalable energy source that’s available 24 hours a day.”

Earlier this year, he added that nuclear power will “absolutely”’ be politically acceptable again given that it does not contribute to climate change like coal, gas, and oil.

Indeed, major countries are already taking steps to increase nuclear energy production.

The Nuclear Energy Agency and the International Atomic Energy Agency estimate total global nuclear power-generating capacity will increase by as much as 56% over the next two decades to 626 gigawatts.

Some of this increase will be driven by the upgrading of existing nuclear power facilities, which will allow them to continue generating power past their original anticipated lifespans.

Most of it, though, will come from new nuclear plants.

China leads the way in building new plants, with 11 currently under construction, followed by India with seven. In total, 93 nuclear power plants are at some stage of development in around 15 countries, including emerging markets Bangladesh, Egypt, Belarus, Ukraine, Turkey, and Romania.

Meanwhile, Japan is slowly bringing back on line some of its 60 nuclear power plants, which were idled after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident in 2011.

In February, the country’s minister responsible for energy said that nuclear power is a key part of the puzzle for Japan—which has more nuclear reactors than any country except the U.S., China, and France—to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

“I think nuclear power will be indispensable,” Hiroshi Kajiyama told the Financial Times in February.

Meanwhile, back in the U.S., the White House’s $2 trillion draft infrastructure plan, announced in late March, calls for funding the development of advanced nuclear reactors. It should be noted that support for nuclear power is bipartisan in the States, with the Trump administration also voicing approval of expanded nuclear production.

What this all means is that demand for uranium is poised to rise…a lot.

There’s a lot of uranium in the earth—40 or so trillion tons of it—but only a tiny fraction of that can be economically mined.

The Central Asian country of Kazakhstan accounts for about 40% of the world’s viable uranium production, followed by Canada (16%) and Australia (9%).

It currently costs miners about $60 to get a pound of uranium from the earth. But right now, they can sell it for only around $28 a pound, down from a high of just over $140 in 2007.

The collapse in uranium prices stems from a misplaced assumption over the past decade that nuclear power would be marginalized by green sources like solar, when in fact it is emerging to complement them.

For the moment, however, miners lose a lot of money for every pound of uranium they extract from the ground. As a result, a lot of uranium mines have stopped producing. And some uranium companies have simply gone out of business.

Decommissioning mines—or starting them back up—is expensive and time-consuming. So, even when demand picks up again, production will be slow to meet it.

Total uranium production was down in 2019 by 12% from levels just three years before. Though final figures for 2020 aren’t available, they will likely show a further sharp decline due to COVID-related closures of uranium mines around the world.

With mines closed, producers are struggling to meet the existing demand…even before the raft of new plants comes online.

In 2015, producers were mining enough uranium to meet 98% of global demand. But by 2018 and 2019, producers were delivering only enough to meet about 80% of demand, according to data from the World Nuclear Association.

Strong demand and constrained supply are a recipe for profitability for the remaining companies producing uranium. But there’s also another reason why money could be about to flow into this sector.

There’s arguably no bigger investment trend today than ESG, or environmental, social, and governance investing. Also called sustainable investing, ESG involves backing companies that score highly in areas related to environmental and societal responsibility. This can encompass everything from environmental protection to fair and safe labor practices and promoting women and minorities to corporate boards.

The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment recently reported that as of late 2020, close to one-third—equal to $17 trillion—of all money professionally managed in the U.S. is being allocated under ESG criteria. That is an increase of 42% from $12 trillion in 2018.

At present, nuclear power and uranium occupy a fuzzy, gray area with respect to ESG. Some ESG investors steer clear of uranium since they lump nuclear weapons together with nuclear power. However, there is a growing acceptance that nuclear will have to play a key role in a greener energy future. And the admission of uranium companies to the ESG world will lead to a big increase in investor interest in the sector.

Putting it all together, investment in uranium is poised to spike. Uranium is one of the few hopes for a low-carbon future. More nuclear plants are being built, while uranium production is down sharply. And the shares of uranium and nuclear power companies will be boosted as more ESG investment funds embrace this industry.

So, investing in uranium is not only socially responsible, but an excellent way to grow your portfolio.

If you’re interested in exploring opportunities in this area, keep an eye on the New York Stock Exchange-listed Global X Uranium Fund (URA). This exchange-traded fund counts two of the world’s largest uranium producers, Canada’s Cameco and Kazakhstan’s Kazatomprom, as its biggest holdings.

Shares in this fund are up 132% over the past year. But if the price of uranium continues to rise, that would be just the beginning for URA. Remember, uranium is at $28 today, but has seen highs above $140 before.

Also worth investigating are the two big, aforementioned producers. Cameco (CCJ) is traded on the New York Stock Exchange, while Kazatomprom (KAP) trades on the London Stock Exchange. More speculatively, Denison Mines (DNN) is a big uranium explorer and developer; it controls a lot of uranium in the ground, but isn’t generating much cash today. So, it may be worth looking into.

Right now, the world is running out of energy…this might be an excellent time to invest in an endless source.

Buying shares of stock has never been easier than it is today.

There are numerous zero-commission brokerages that allow you to sign up and start trading, often in just a few minutes. (I use and recommend Fidelity, though Charles Schwab and E*Trade are fine choices; steer clear of the gamified services like Robinhood and Webull.)

However, the key to successful investing is not only knowing how to buy, it’s knowing how, when, and why to sell. And it’s the how part of this selling equation that often gets overlooked.

Let me explain…

Recently, I made a nice profit on shares of AgEagle, a company focused on delivering advanced commercial drone technologies in the agricultural arena.

I bought in when the price was about $4 per share, amid rumors that Amazon, in its pursuit of drone-based package delivery services, might team up with AgEagle. As anticipated, bullishness quickly enveloped AgEagle shares, and over a two-month period the price soared to a new high of nearly $15.70.

That’s a huge move in a short span—a move that likely wasn’t sustainable. So, I decided to put a “trailing stop” on my shares to protect some of my profits.

Trailing stops are the preferred strategy of savvy investors. They are a simple, easy-to-implement way to limit the damage from faltering positions before your losses grow too large. Yet at the same time, they also allow your winning positions to keep on winning.

Here’s how they work: Say you buy a stock at $100 per share and set a trailing stop at 20%. If the share price tanks immediately, your shares will be sold automatically when the price drops by 20%…so in this case, to $80.

However, if the price starts to increase, your automatic selling price will follow the shares higher. Say, for instance, the share price doubles to $200. Now, your exit price is $160—20% below the new high of $200.

For my recent AgEagle trade…new rumors began to swirl casting doubt on a potential Amazon tie-up. I wanted protection, but I also wanted the ability to let my shares run higher, in the event the Amazon deal turned out to be real.

At that point, I was up a lot and I was willing to give up 30% of that gain in the event the shares collapsed. So, I set a trailing stop loss of that amount in my account.

Then, not long after, the new, negative rumors about Amazon freaked out the market and AgEagle shares dropped like a flag losing its breeze. They fell from about $14 to just under $9—in a single day.

The cliff dive activated my trailing stop, and I sold automatically, getting out at just north of $11 per share. I gave up about $4 of upside, but my profit was still 175% in just two months.

I didn’t sell at the top price, but that was never my intention.

On Wall Street, pigs get fat, hogs get slaughtered.

I can’t call the exact price at which a share will top out. No one can. So, I would rather have a trailing stop in place and give up some portion of my gains than risk something far worse: getting out way too early.

Imagine, for instance, if I had somehow guesstimated the top-out price and sold at $15.70. Then, suddenly, Amazon announced it was going to exclusively use AgEagle drones for delivery…and the company’s shares soared to $150 from $15.

By fearfully locking in a few extra dollars per share when the negative rumors emerged, I would have given up potentially life-changing gains. That’s the sort of trade that haunts you.

However, if AgEagle does retreat (as it did), I’m protected. I sell at a price I’m comfortable with and I still pocket gains of 175% in two months…and no one can complain about that.

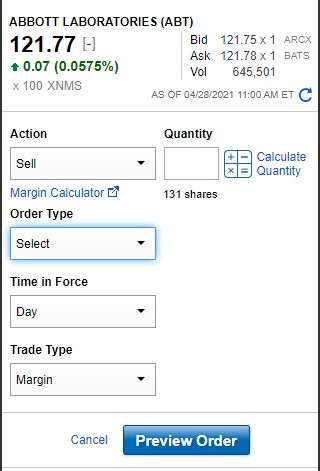

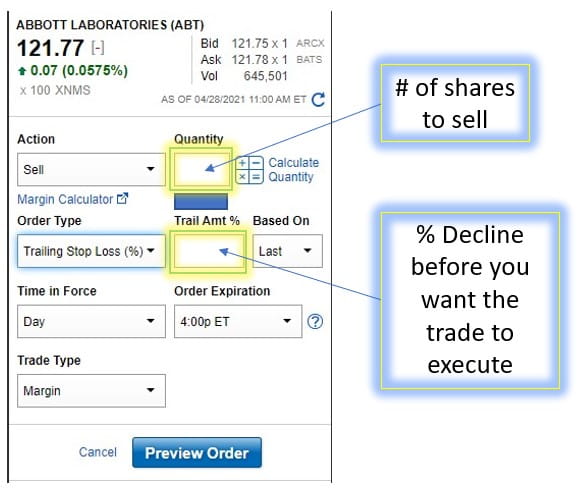

I’ll likely ask you to set trailing stop losses on some of our future recommendations, so I thought I’d show you how it’s done. It’s very simple. I’ll use my Fidelity account as an example (your account might be different, but the process will be very similar).

Step one: Head to your “Trading” page. Mine looks like this:

Select from your portfolio the stock you want to sell. In this example, I’m setting up a trailing stop loss to exit Abbott Labs. (Note: Abbott is not a recommendation. I’ve owned Abbott since it was less than $8.30 per share, so there’s no way to replicate my trade now. Also, this is just an example; I am not selling Abbott.)

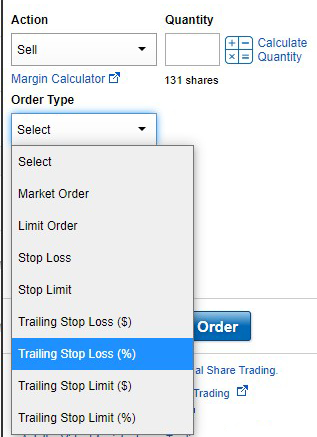

Step two: Under “Order Type” select “Trailing Stop Loss (%).”

Step three: Fill in the quantity of shares you want to sell, and then set the trailing % amount.

Where to set the percentage decline will vary. With AgEagle, a new position that moved rapidly higher, I was willing to give up 30% on a pullback because I knew I would still lock in big gains. I wanted a good deal of leeway to let a volatile stock bounce around without kicking me out of the position too quickly.

But you might also want to use a much smaller trailing stop of, say, 5% or 10%, on a brand-new position in a volatile stock that hasn’t moved up rapidly. That will limit your losses in the event your timing was wrong and the shares tank.

And with long-established positions in highly stable companies like Abbott Labs, I might set a stop loss of, say, 15%. I have massive gains in that stock, so a 15% pullback won’t faze me, and an established company such as Abbott shouldn’t fall that sharply unless we’re in a bear market or unless Abbott announces bad news of some sort.

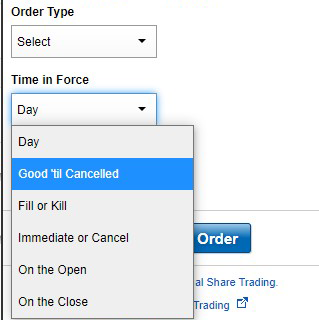

Finally, the fourth step: Select “Good ‘til Cancelled.” That keeps your order rather than letting it expire after the end of the day.

After setting your parameters, make sure all is correct, and place the trade. You’re set.

My AgEagle trade aside, there’s another reason trailing stops are on my mind of late and that is crypto’s turbulence in April.

After a hype-filled period in which the popular exchange Coinbase listed on the New York Stock Exchange at a ludicrously overpriced valuation of $86 billion (I shared my thoughts on the subject in a Field Notes mailing, which you can read here), most cryptos retreated in the second half of the month.

First, bitcoin, along with other major tokens, experienced a flash-crash on April 17, falling nearly 14% in an hour before rebounding. This was caused ostensibly by a power outage in China, where a lot of bitcoin is mined, as well as an unconfirmed rumor on Twitter that the U.S. Treasury Department is going to crack down on money laundering through crypto.

Then, about a week later, there was another crypto selloff, spawned by reports that the Biden administration is planning to raise capital gains taxes.

At this point, allow me to assuage any fears you may have. These events will have basically no impact on the crypto market long term.

Even if the Treasury Department rumor is true, which it likely isn’t, any measures would have little to no effect on institutional and Main Street investors. And the Biden tax proposals, though excessive, would impact only Americans who make over $1 million a year.

Right now, since savings and bonds offer near-zero or below-inflation returns, the cash flowing through the economy has nowhere to go but stocks and cryptos. So, I expect the crypto market to register significant growth in the months ahead.

As an old crypto head, I’m used to this sort of instability. The crypto market is wildly volatile, and particularly after prices set new highs, which they did earlier in the month when bitcoin hit $64,829 on April 14.

Which brings me back to my main point…trailing stops do not work for cryptos (unless you are a day-trader) since you risk getting “stopped out” of your position, only to watch the price race higher.

Bitcoin’s current run is a prime example. If you had bought bitcoin at the start of this year and decided to place a 30% trailing stop on your investment, you would have missed out on big gains.

On Jan. 8, bitcoin reached a then-record high of near $42,000. However, by Jan. 27, it had fallen again to around $29,365, meaning a 30% trailing stop would have been activated and you would have sold your crypto…missing out on bitcoin’s subsequent rise.

Or consider Ethereum—the largest holding in my crypto portfolio.

On Feb. 20, the crypto was trading at $2,030 per coin. Eight days later, it was down to $1,316—a drop of more than one-third that, again, would have activated a trailing stop loss order of 30%. But even after the recent instability, Ethereum is trading above $2,500.

So, even a large stop loss margin of 30% can be damaging, rather than protective, when it comes to crypto.

Over the last 12 months, bitcoin and Ethereum have risen more than 550% and 1,100%, respectively. Assets that rise this fast, in such an emerging space as cryptocurrencies, will inherently experience wild price swings.

Understanding and accepting this volatility is an essential part of successful crypto investing.

■My in-depth reports on bitcoin and DeFi will soon be ready…and you’re getting them for free as part of your subscription.

First up, a major announcement. As I’ve mentioned in my Field Notes mailings, I’ve been working on a big project to help you understand and profit from the cryptocurrency revolution. In the coming weeks, I will be ready to unveil it to you.

This project comprises four, brand-new reports explaining key aspects of the emerging crypto space, and providing my specific recommendations for what to buy and how and where to invest.

The first of these reports will be my comprehensive guide to bitcoin.

This exhaustive report details the origins of the crypto, explains the blockchain technology behind it, and most importantly, highlights where bitcoin is headed…including my buy recommendation and price prediction for bitcoin this year and in the years ahead.

It also includes an easy-to-follow, step-by-step guide on how to buy bitcoin through my recommended cryptocurrency exchange. It’s everything you need to know about owning and profiting from bitcoin.

The second of my new reports is an in-depth guide to decentralized finance, or DeFi—a revolution that is poised to transform the world of banking, in the same way that the internet fundamentally altered the world of commerce.

My report will show you how you can easily and safely earn 8.6% interest a year, simply by stashing money in what are effectively crypto savings accounts. Plus, I’ll show you another safe, easy-to-understand strategy I use to further boost this yield, potentially by three or four times! (Again, I have a simple guide, complete with step-by-step images, on how to do this.)

Also in my DeFi report, I’ll recommend other cryptocurrencies you need to own, besides bitcoin, that I anticipate will see big gains within the next three to four years.

All of the recommendations in these two reports—spanning my recommended cryptos and the crypto-savings accounts—will also be added to our portfolio tracker on the website so you can easily find them and review their progress any time you like.

The other two reports are shorter, but highlight important, little-known aspects of the crypto space. The first discusses a way to own gold through cryptocurrency—a strategy that might just be the cheapest and easiest way to buy, move, and store gold today.

The final report delves into the issue of privacy and cryptocurrencies, and explains a special kind of crypto called privacy coins that allow you to buy and sell cryptocurrencies anonymously.

Remember, these reports will be available to you for free as a subscriber to the Global Intelligence Letter. They’re my way of ensuring that all of us can profit from cryptocurrencies and the blockchain revolution that is poised to transform our world.

Stay tuned…

■There’s a new way to buy crypto, but you shouldn’t use it.

Speaking of the crypto financial revolution, the popular payments app Venmo announced on April 20 that it’s begun allowing its roughly 70 million users to invest in cryptos with as little as $1.

The company said it launched the service to demystify crypto and give users a simple way to invest. This story comes a month after Venmo’s parent company, PayPal, introduced Checkout With Crypto, which allows U.S.-based users to make purchases with digital currencies.

I bring up this story not to recommend that you buy cryptos through Venmo. You shouldn’t. The app offers access to just four coins and doesn’t allow you to withdraw or earn interest on your cryptos (and yes, you can earn interest on bitcoin and other cryptos, as I will explain in my DeFi report).

No, I bring up this story to point out how integrated cryptos are becoming in our society. In virtually every arena, from payments to politics, crypto is gaining ground.

Consider that banks closed a record 3,324 branches across the U.S. last year, as financial services moved increasingly online and into the DeFi realm. Or consider a proposal in Alaska to develop a blockchain-based voting system…a move that would make polls ultra-secure and unhackable.

The blockchain revolution is here. This is the time to invest and profit, and my reports will show you how to do just that.

■A 20% interest rate on your savings? Yep—no lie.

As evidence of the blockchain revolution, all around the world these days, central banks—including our very own Federal Reserve—are researching, building, or launching digital currencies to replace physical fiat currencies. This is the future: a digital dollar, a digital euro, and so on.

But already, doppelgängers exist. They’re called “stablecoins” and they shadow fiat currencies. Which means they don’t bounce around with the crazy volatility we’ve seen with bitcoin, Ethereum, and others. They hang out at $1—rarely venturing more than half a penny in either direction. They are, as their name declares, “stable.”

Better yet, they pay interest, not unlike a savings account or certificate of deposit.

For about a year now, I’ve been stashing some of my crypto assets in various stablecoin investments just to collect the supercharged interest rates. And with my latest account—at Anchor Protocol—I’m collecting 20%.

Yes—a 20% annualized interest rate on a digital stand-in for the dollar. I don’t risk loss of capital. I just stuff my money into my account that holds the equivalent of e-dollars and I collect a monster interest rate.

There’s no lock-up period; I can pull out my cash whenever I want. This is the world of decentralized finance, and it’s the future of savings, here today.

■This free app can help you score big discounts on airfare.

If you’re itching to start traveling again, then there’s an app that can help you get a great deal on flights. It’s called Hopper and it works by using an algorithm to predict when airfares will drop in price.

Through the app, which is free on iOS and Android, you can register for price alerts on flights to and from specific destinations at specific dates. The app will then recommend whether to buy now or wait for prices to drop…thus helping you deal with that always difficult buy-now-or-wait dilemma. The app can also track prices for hotel and car rentals.

To get started, just select your departure airport, destination, and dates. You have the option to buy tickets through the app. Alternatively, when you receive a price alert, you should be able to find the same deal on the airline’s website.

■West Virginia is offering to pay remote workers $12,000 to move there.

Muscle Shoals, Alabama and Tulsa, Oklahoma have made headlines in recent years by offering relocation grants of up to $10,000 to attract remote workers. Now, West Virginia is joining the fray with an even more generous offer.

Under the Ascent WV program, remote workers who relocate to the Mountain State can collect $10,000 in cash during their first year and $2,000 during the second year. They will also have access to a free remote working space and more than $1,200 worth of complementary outdoor gear rentals.

Applicants must be working remotely, or have the ability to work remotely, for a company based outside of West Virginia, or be self-employed outside the state. They must also be U.S. citizens or residents.

Applications are now being accepted for Morgantown, the first participating city in the state, with applications for Lewisburg and Shepherdstown set to open later. You can find all the details on the Ascend WV website here.

■Do you ever suspect your internet is slower than it should be? Well, the FCC wants your help to investigate.

The Federal Communications Commission is trying to gain an understanding of real internet speeds in the U.S. As part of this mission, it’s asking the public to download and use its FCC Speed Test app.

The idea is to create a user-generated database of internet speeds, rather than relying on data provided by the big internet service providers, which let’s face it, could well be painting a rose-tinted picture.

According to the FCC, more accurate broadband maps will help it identify which towns and neighborhoods need funding for better internet services.

Plus, as a consumer, if you feel you’re not getting value for money from your internet provider, the app can provide you with independent data to back up your claim when you contact customer service.

The app is available for iOS and Android. It comes with several speed tracking features, including a chart that’ll plot out your speed tests over time, and a mapping function that can break down your phone’s speed tests by location.

■If you feel like your blood pressure is always higher when measured at the doctor’s office, it might not be your imagination.

High blood pressure is a leading risk factor for heart attacks and strokes, so having a true idea of your blood pressure is very important. However, several authoritative studies have shown that people regularly record higher blood pressure readings at the doctor’s office, which can lead to false diagnoses or overmedication.

A big reason for the inaccurate readings is something called “white-coat syndrome.” People naturally feel more anxious when seeing a doctor and this raises blood pressure.

Other reasons for the higher readings may be that people often rush to make doctor’s appointments (you should rest for a few minutes before a test). Or busy nurses or doctors take shortcuts when measuring blood pressure, such as by taking readings through clothing (even a thin blouse or shirt sleeve can affect the results) or while patients are lying back in chairs (you should always be sitting upright with your back supported).

If you feel you’ve been given an inadequate or inaccurate test, be assertive and ask for it to be taken again. This may include taking a short break of a few minutes to relax, while resting your arm in a comfortable position.

In 2018, hypertension was a contributing factor or the leading cause of about half a million deaths in the U.S. This is an area where you want to make sure your test results are accurate.

■I’ve been doing this wrong my whole life…and I bet you have, too.

Back in college, I was a lacrosse player, so I couldn’t begin to estimate the number of times I’ve used an ice pack on sore muscles, or been ordered by a coach to jump into a dreaded ice bath after a game. Well, it turns out…that’s all nonsense.

New research published in the Journal of Applied Physiology shows that icing muscles after strenuous exercise may in fact damage the healing process rather than aid it. The new study involves mice, not people, but it’s the latest in a growing body of evidence, including a 2015 survey of weightlifters, to find that icing muscles after exercise is actually damaging.

So, if ice packs are out, what should you do to prevent swelling and soreness after a strenuous workout? Well, nothing, it seems.

Swelling is the body’s natural response. It’s your cells getting on with the business of healing damaged muscles. According to the research, the best thing we can do is leave the ice packs in the freezer and let the body do its thing.

Thanks for reading and here’s to living richer.

Jeff D. Opdyke, Editor

Global Intelligence Letter

© Copyright 2021 by International Living Publishing Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction, copying, or redistribution (electronic or otherwise, including online) is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of International Living, Woodlock House, Carrick Road, Portlaw, Co. Waterford, Ireland. Global Intelligence Letter is published monthly. Copies of this e-newsletter are furnished directly by subscription only. Annual subscription is $149. To place an order or make an inquiry, visit www.internationalliving.com/about-il/customer-service. Global Intelligence Letter presents information and research believed to be reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. There may be dangers associated with international travel and investment, and readers should investigate any opportunity fully before committing to it. Nothing in this e-newsletter should be considered personalized advice, and no communication by our employees to you should be deemed as personalized financial or investment advice, or personalized advice of any kind. We expressly forbid our writers from having a financial interest in any security they personally recommend to readers. All of our employees and agents must wait 24 hours after online publication prior to following an initial recommendation. Any investments recommended in this letter should be made only after consulting with your investment adviser and only after reviewing the prospectus or financial statements of the company.