Dear Global Intelligence Letter subscriber,

Just up a slight incline from the Limmat, the river that cuts through Old Town Zurich, you’ll find Splendid Piano Bar tucked into an alleyway. It’s the kind of bar built for regulars. A small, red-carpeted space. Grand piano, dead center. Every night, jazz and classic rock spill forth and the locals sing along to famous standards in both English and Swiss German.

Although it’s been around since the early ’50s—when it was known as the American Bar—Splendid has something of a 1920s, speak-easy vibe. You almost expect that the ghost of Flappers past might materialize on the wrought-iron, second-floor balcony.

On a cold winter’s night, the combined body heat in there will certainly make you forget about the snow frosting the alley outside, but good luck moving around freely.

On many an occasion, I’ve sat on a bar stool at Splendid—or, more commonly, stood—with a gin and tonic or some drunken coffee as my friend, Rob Vrijhof, held court.

Until recently, Rob ran WHVP, a Swiss money-management firm, where I’ve housed my largest retirement account for nearly a decade. Rob is gregarious and outgoing. A booming laugh. Always has a joke. Always has a story.

As a routine, we’d have dinner at Real, a Spanish eatery in Zurich that, oddly, has the best Stroganoff I’ve found outside of Moscow’s Café Pushkin. Afterward, we’d regularly end up at Splendid, to warm up—inside and out.

We’d talk about life, investing, or Rob’s latest motorcycle adventure or upcoming vacation to some Southeast Asian beach. But we’d inevitably come back around to the dollar and our shared view that if Uncle Sam’s money were the currency of any other nation, it would devalue quickly.

Those conversations over the years, and the subsequent meetups Rob and I have had in places as varied as Las Vegas, Cabo San Lucas, and Montevideo, shape the inaugural issue of my Global Intelligence Letter.

For more than a decade now, I’ve contemplated what’s next for the U.S. dollar. I don’t mean “next” in terms of tomorrow. Currencies move in grand, sweeping arcs that stretch over years, sometimes a decade or more.

Right now, we are in the midst of a long-term dollar decline that began in late 2016 and which, statistically, should last until sometime between 2023 and 2026. But I expect this time will be different—that the wave will bottom out later this decade, likely 2027 or 2028.

Ultimately, I see the dollar losing 55% of its 2016 peak value.

If you’re on the wrong side of that trend, almost everything in your life will become more expensive—potentially painfully so. You will lose purchasing power. However, set yourself up on the right side of that trend and, well, your wallet will grow fatter and you will protect your wealth from inflation and, at this particular moment in history, side-step the debt crisis that the U.S. will have to confront before this decade is over.

How does Switzerland fit into this? It’s part of the solution.

I house my biggest retirement account in Zurich, Switzerland.

The Eternal Alliance of the League of the Three Forest Cantons established the nation of Switzerland in August 1291. I know this obscure fact only because, for a while, I designed investment products for a small Swiss insurance firm. I learned a lot about Switzerland during that period.

One of those lessons revealed why it is that the Swiss franc emerged as a so-called “safe haven” currency—one of the very few currencies in the world that savers and investors flock to in times of global dyspepsia.

This trend dates to the 1930s, the inter-war period, when Europe was awash in political and financial turmoil as new countries emerged from the destruction of empires at the end of World War I, and as dictators took the reins in various nations.

At that moment, Switzerland, a country that had pledged its eternal neutrality in 1815, introduced a law that imposed a heavy punishment on any banker who dared divulge information about any holder of a Swiss bank account.

That codified a practice begun 20 years earlier, in the run-up to World War I, when Swiss banks began offering the long-glorified “Swiss numbered account” to wealthy Europeans looking to hide their money.

Swiss bankers attached no names to these accounts, just a number, sometimes a code word. That secrecy insured that foreign governments seeking to tax or impound their citizens’ offshore wealth could not demand Switzerland produce the names of account holders. Neither the Swiss government nor Swiss banks had that information to produce.

As an accidental side-effect, that secrecy also ensured that the Swiss franc would become one of the world’s true safe-haven currencies. People fearful of currency devaluation in their home country had a destination to safely store their money. Same with people who feared war. Or those who feared wealth confiscation. Or egregious government taxation.

Whatever the reason, people from all over the world—from average Joes to warlords, kingpins, dictators, and U.S. congressmen—learned to stash their cash in anonymous, numbered accounts in a mountainous country in the center of Europe. All were comforted by a simple fact: Prying eyes would never find their wealth.

Today, Swiss numbered accounts still exist, but, frankly, they’re not tremendously beneficial. Global “know your customer” rules now demand all Swiss accounts be attached to an identifiable person. Moreover, depending on the situation, Swiss authorities these days will turn over account information to government investigators.

But the franc...it remains one of the world’s three safe-haven currencies to this day, along with the dollar and the Japanese yen.

And it’s where I’ve recently put 75% of the multi-six-figure retirement portfolio that Rob’s firm manages for me. It’s also why I’ve added substantially to my gold holdings. And though this might seem like a non-sequitur investment, it’s why I’m moving into the Norwegian krone as well.

I will connect all those dots in a moment.

First, let me tell you that…

I can see the future.

It looks very much like the past.

And I don’t mean the last couple of years or decades, or even the last century or so. I mean the past that pretty much defines human history.

The thing about humans, especially those in government, is that they always make a hash out of a country’s money. That’s been the arc of empires and nations for thousands of years. Is anyone really gullible enough to believe that the clowns running the circus that is the modern U.S. government are exceptionally better at governing than the clowns who ruined the Roman Empire? Or those who destroyed money in Weimar Germany? Or Argentina…Hungary…Greece…Ukraine…Nicaragua?

The list goes on.

Then there’s the modern Federal Reserve. It might have modern monetary tools to (try to) manage modern dollars and a modern economy, but debt isn’t modern. It’s not a newfangled form of finance that demands an MBA and secretive, black box computer models to manage. Debt is as old as dirt—or, as old as the Sumerians, who seem to have invented it nearly 5,000 years ago.

There is no “managing” debt. Debt manages you. You repay what you owe, or the financial equivalent of a beefy Italian named Shorty shows up with a baseball bat to break your kneecaps. You and I call it default or bankruptcy. Governments and companies like to call it “restructuring,” as though that bit of verbal makeup pretties up the underlying fact that you have overspent your capacity to pay, and Shorty’s on his way.

That’s what I worry about for the U.S. dollar. It’s a worry I’ve been writing about for a decade. During that time, the problem has worsened. I’m not the only one who sees this.

That massive rise in the value of bitcoin since last summer…it’s based as much on worries about debt and our fiat currency—the dollar—as it is on excitement about crypto’s potential. Just read what Elon Musk tweeted in February, shortly after his electric car company, Tesla, bought $1.5 billion in bitcoin: “When fiat currency has negative real interest, only a fool wouldn’t look elsewhere.”

That’s a damning comment. In no uncertain terms, Musk is saying that a digital currency that has been around for only a decade is less foolish to own than a physical currency that has been around for more than 200 years. And he put down $1.5 billion for the win.

China’s betting against the dollar, too. So are the Russians. And our allies in the European Union.

You probably know America owes a boatload of money to China because China owns a boatload of American debt. What you might not know is that China has been selling huge sums of U.S. debt in recent years.

The U.S. Treasury Department reported that China owned $1.07 trillion of Uncle Sam’s bonds as of December 2020. In the summer of 2015, the number was $1.84 trillion. China has cut its dollar exposure nearly in half. And it has been importing tons of gold through Hong Kong for at least the last decade now as it builds an ever-larger financial fallout shelter to weather a dollar storm.

Russia, meanwhile, has dumped so many dollars that gold now surpasses the greenback inside Russia’s central bank holdings.

And then there’s the European Union. It’s pushing to boost the euro’s role in international trade settlements. Basically, that’s countries and companies buying and selling across borders. That has been the dollar’s playground for decades, since the dollar is the currency in which global trades are priced. The EU, weary of that situation, is now angling for change.

A photo I took of Moscow’s financial district on a visit to the city in May 2019. Russia and China have both been selling vast sums of U.S. debt in recent years.

I realize that for most Americans, none of that means very much. And I understand why: We don’t directly feel the effects of any of this. We don’t sense what a weak dollar means to our daily lives. There’s a reason for that.

Status quo bias—that’s what behavioral-finance experts call it.

You probably know the story about the Thanksgiving turkey who spends every day well-fed and well-pampered. And that turkey thinks he’s living the dandiest life. Until the day it all stops.

That is status quo bias. It’s the idea that every today generally looks like every yesterday, and so will every tomorrow. We humans think this way because we can’t grasp, much less calculate, all the moving pieces in play that could make tomorrow very different from today.

In terms of the dollar, we’re blinded by our status quo bias. The dollar has been “King Dollar” for at least 70 years, the result of a 1944 gathering of global pooh-bahs at a hotel in Bretton Woods, Vermont. They all agreed that in a post-war world, the dollar would be true north—the currency by which every other currency steered. Most of the 330 million Americans alive today have never known any other world.

Alas, few Americans understand what that really means.

Nor do they understand the damage it will cause when that reality changes.

Right now, as you’re reading these words, hundreds of billions of dollars in commodities are moving around the world. No matter whether it’s milk powder moving from New Zealand to China, or coffee moving from Colombia to Hungary, or natural gas flowing from Qatar to Japan, all those trades are priced in U.S. dollars. It’s the world’s “reserve currency,” the currency that lubricates global trade.

As Americans, that gives you and me an unfair advantage relative to just about every other consumer on the planet.

We don’t have to worry about currency conversion since the dollar is the yardstick in every trade.

Here’s why that’s important to your pocketbook…

Imagine you’re Japanese. Your homeland is almost wholly dependent on oil imports. Imagine global oil prices have risen from $50 to $55 per barrel, a modest 10% increase that wouldn’t do much to impact you.

But imagine as well that the currency in your wallet, the yen, has plunged 16% in a matter of months (which the yen did in 2016). That barrel of oil that costs the U.S. 10% more now costs your country 31% more.

The oil is no different. It’s the same 55-gallon barrel. But because the dollar is the official measure in which oil trades, and because your country’s currency has fallen relative to the dollar, you, a Japanese citizen, see your wealth shrink much faster than an American.

You have to spend more just to live your daily life because everything you buy in Tokyo that comes from a petroleum byproduct is more expensive: gasoline, paint, cosmetics, synthetic clothing fibers, synthetic rubber, bubble gum, shampoo and hairbrushes, toothpaste and toothbrushes, smartphones, shoes, dishes, pillows, soft contact lenses and eyeglasses, aspirin, soap. The list is huge.

And that’s the knock-on effects for just one commodity—oil.

So, imagine a day in which King Dollar no longer sits on his throne. A day when the greenback is no longer true north, but just another currency, albeit still an important one. Our dollar-based daily living costs are going to rise dramatically.

Ah, Jeff! Therein lies the rub. Why would King Dollar lose his throne?

In a word: debt.

I told you the tale of the Thanksgiving turkey. I’m sure you also know the story of the frog in a pot of water set to a slow boil. That little frog is relaxed, incapable of sensing the slowly rising temperature that’s about to turn him into a stew. He can’t perceive the minute changes that happen over a long period of time because his body continually adjusts to the rising temperature.

Which takes us back to the year 2000…

The U.S. was coming off the booming Clinton years. Government recorded a budget surplus for the first time in eons (and, it turns out, the last time, too). Uncle Sam required so little debt that the Treasury Department stopped selling 30-year bonds because the government had no need for the money. At that moment, Uncle Sam’s debts amounted to about 55% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), America’s total economic output in a single year.

Now I want to show you a frog boiling in water…

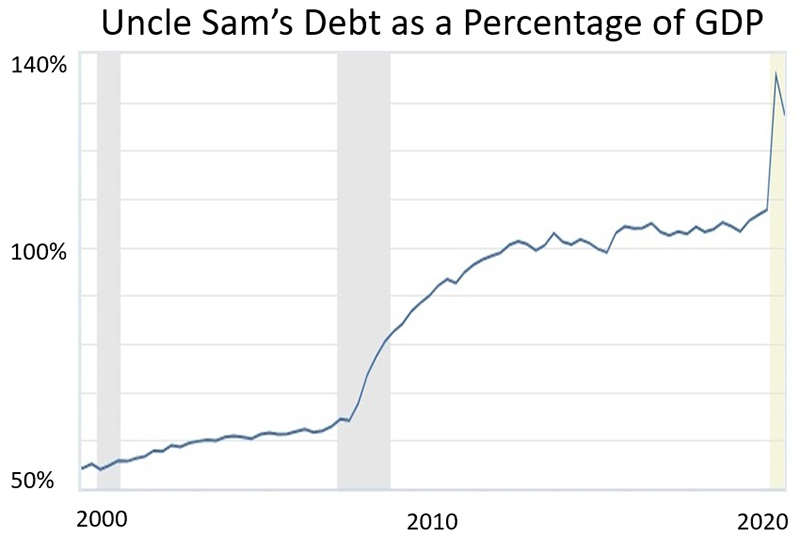

See the chart below. It shows U.S. debt since 2001. In just 20 years, we’ve moved from a healthy, manageable 55% to 130% of GDP today.

America’s debt is one-third larger than the amount of money every American business and every individual American produces in a year. That’s not sustainable. Worse, economists will tell you that once you move into the 60% to 100% range, your country is heading for trouble.

And America’s trouble is about to worsen.

As I write these words, Congress is debating another COVID-related stimulus package of roughly $2 trillion that would push debt to about 140% of GDP. That would be about $30 trillion, the largest sum of debt in all of financial history.

Emphasizing what $30 trillion means is challenging because the sum is so preposterously large that we can’t begin to process the enormity. We have no reference. But let’s try this: If you were to spend $1 million a day, every day, from the day you were born until the day you die at 100 years old…you would need to live 822 lifetimes.

I don’t care if you are the world’s largest economy with the world’s most important currency, that kind of debt is a warning sign.

Right now, we’re high up in the mountains, on an ice-slicked road too narrow for the semi-tractor trailer Uncle Sam is drunkenly driving.

At night.

With no headlights.

In short: There’s a crash coming.

But before that crash arrives, the dollar will experience a long-term down trend. In fact, that trend has already begun. I have another chart I want you to see…

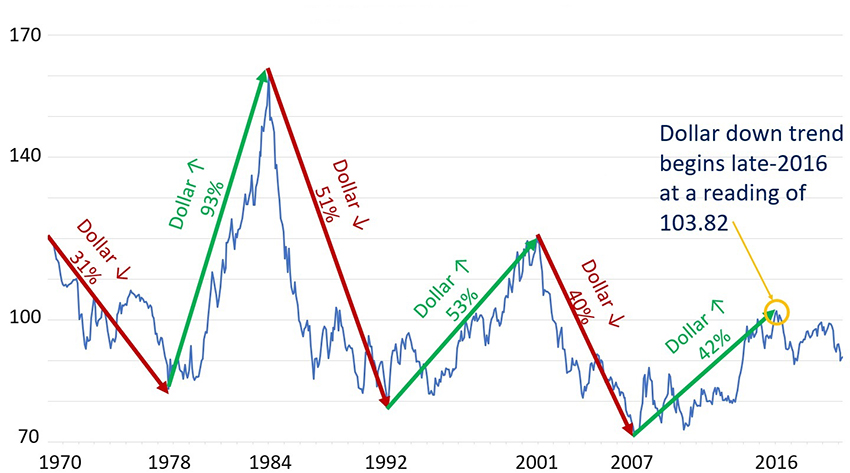

I call this my Dollar Wave chart. The blue line is the U.S. Dollar Index. It simply tracks our greenback against a basket of major world currencies. Up means the dollar is strengthening against those world currencies. Down means the dollar is weakening. You can plainly see those sweeping trends I mentioned. We care about them because they represent opportunities for profit and wealth preservation that we can exploit.

Two facts I want to point out to you on this chart.

Here’s how I connect those two facts: The current dollar trend—a downtrend—began in late 2016 with a Dollar Index reading of just over 103. We are now just over four years into a trend that statistically should last until late 2023 or early 2026. And based on historical precedent, the Dollar Index should end up between 50 and 71.

I emphasize “should” in those previous sentences because I am not convinced this time will be typical. Indeed, I know this time will be very different.

The size of America’s debt, the extraordinary partisanship in government, the dynamics of an economy fundamentally changed by the pandemic, budget deficits stretching years and years into the future, and a global push to reduce (maybe even eliminate) the dollar’s primacy will see the greenback sink to unimagined lows.

My expectation: The Dollar Index ultimately falls to 47. It’s currently at 90. So, I’m predicting a 48% drop from today’s level. Moreover, I’m saying the current dollar decline will stretch until later this decade, sometime around 2027, maybe 2028.

Government is slow to respond to crises; just look at the ongoing Social Security crisis that has been kicked down the road over and over again. Politicians fearful of the impacts that necessary solutions will have on their constituents are loathe to vote themselves out of a cushy job. They will respond to a dollar crisis only when the crisis is clear—when the crash is unfolding.

All of which brings us back to the Swiss franc, gold, and the Norwegian krone.

At 55 years old, I’m not willing to risk having my retirement wrecked when Uncle Sam’s profligacy comes home to roost.

Every nation—every empire—that has ever overspent its means ultimately suffered a reckoning with debt. They all found ways to paper over the crisis for some period of time. But as I noted earlier, debt is barbarous. You repay it, or debt messes up your life. No matter what kind of financial wizards you hire, those options remain the only two you have.

Alas, I see no path for the U.S. to repay her monolithic debts. So, we’re left with “debt messing up your life” as the only logical path forward.

The point here is that Congress has been running budget deficits of between $400 billion and $3.7 trillion for the last decade. That’s money we don’t have. How do we get it? The Treasury turns it into debt, which is why U.S. debt has exploded to levels that will never be repaid.

To pay down even a little of the existing debt Uncle Sam currently has would require one of two facts to be true: Either Congress would have to slash spending. That’s not happening. Or the U.S. economy would have to start growing so fast that Congress has not only enough tax revenue to run the country, but extra left over to begin paying off the debt. Achieving the kind of growth required for this is next to impossible.

It’s the Law of Large Numbers. Turning one penny into two, a 100% gain, is simple because the starting value is so small. Turning $21.3 trillion (the size of the U.S. economy) into, say $23.4 trillion in a year, just a 10% increase…that’s damn near unachievable.

Large, mature economies simply don’t grow that quickly. In the last 30 years, the fastest the economy has grown is about 4.8% a year, and that was back in the late ’90s, those halcyon Clinton years. So far this millennium, we’ve topped 3% just once.

As such, we will confront a debt crisis at some point later this decade. And because the dollar will be at the center of the crisis, it will not be a safe-haven currency people rush to. It will be a currency people flee!

Where will they go?

Well, the Swiss have a long history of financial prudence. Where governmental debt in the U.S. will soon hit an unsustainable 140% of GDP, in Switzerland it’s about 41%—so relatively miniscule it’s like you expect the Swiss could pay off all their debt with some pocket change found beneath the couch cushions of a high-end ski chalet in St. Moritz.

In the last four decades, Swiss debt-to-GDP never reached 60%, and it spent the bulk of those decades in the 30% to 50% range. In short: The Swiss manage their spending as though spending and saving actually matter.

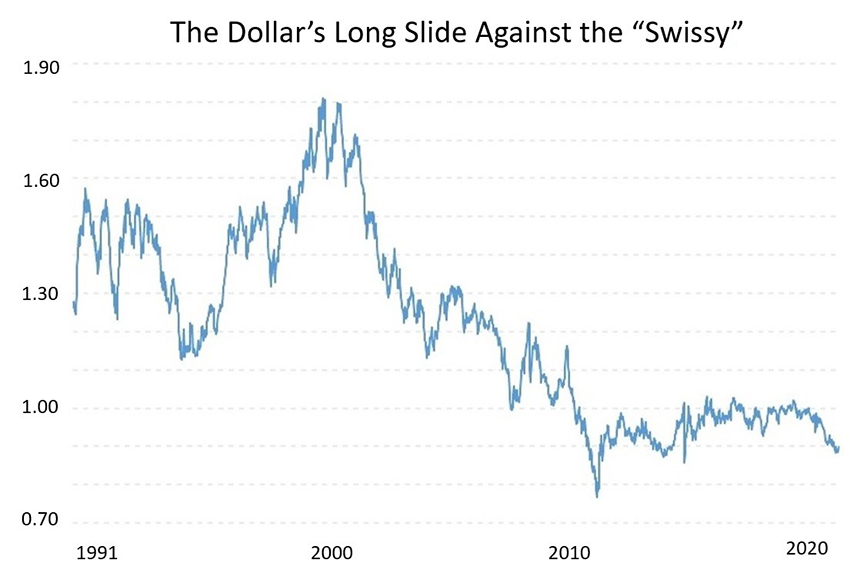

In turn, the “Swissy,” as the franc is known in the currency world, has a long history of gaining value against the dollar. Or said another way: The dollar has a long history of losing value relative to the Swissy. Here’s the picture of what that looks like…

That trend will continue…which is why I have put so much of my retirement account into the Swiss franc. It protects me against a longer-term decline in the dollar. It means that in dollar terms, my wealth will be larger when I one day convert my francs into greenbacks to afford my retirement expenses.

And when the dollar-debt crisis begins, you can bet the franc will surge in response. So, it’s a currency insurance plan, too.

Others apparently see value in this strategy as well. Interactive Financial Advisors earlier this year

announced in Securities and Exchange Commission filings that it had purchased $3.4 million worth of the Swissy, taking the firm’s franc holdings to nearly $14 million.

Others who have jumped into this sandbox include:

They’re all buying exactly what I bought back in July: Invesco CurrencyShares Swiss Franc Trust (FXF).

FXF is an exchange traded fund (ETF) you can find on the New York Stock Exchange. It’s designed to track the Swiss franc’s movements relative to the dollar. As the dollar declines vs. the franc, FXF goes up.

I see this as a long-term holding. This is, after all, currency, and currency doesn’t move in huge spurts. It meanders.

And slowly but surely, FXF will meander higher as the long-term dollar down wave rolls over us.

I won’t offer you a “buy up to” recommendation because it’s a currency ETF that simply tracks the franc’s movements.

Instead, I will say trade out of as many dollars as you’re comfortable with. For me, that’s 75% of my primary retirement portfolio. For you, it might be different. And again, plan on holding this. This is not a quick-profit trade. It’s a long-term, strategic investment to position yourself for long-term dollar weakness.

Along with the franc, there’s gold. It, too, will be a winner as the dollar declines.

Gold, for me, protects against two eventualities, both of which are front and center in my planning:

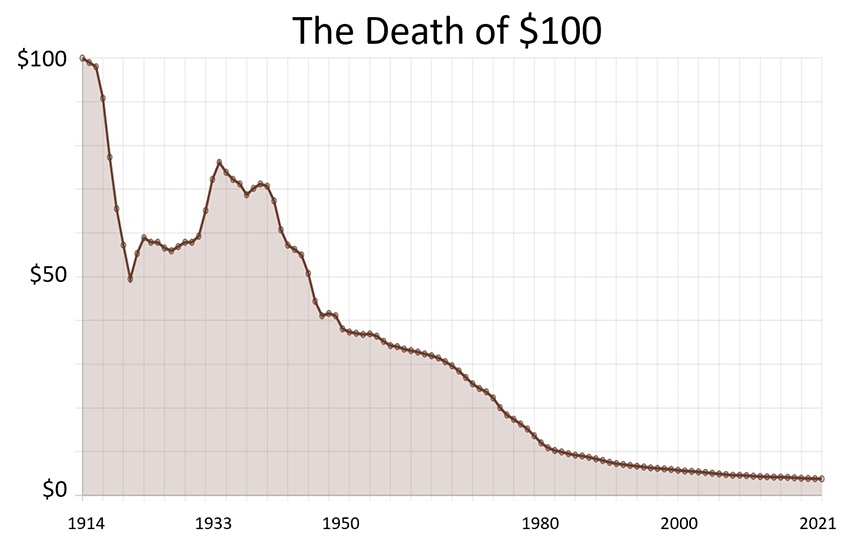

Let’s start with inflation, and yet another chart…

This chart shows the value of $100 since 1914. This ski slope is the destruction of wealth. It’s inflation and how much value $100 has lost in the 107 years since the Federal Reserve was created to manage America’s money. The Fed is the Three-card Monte expert in this hustle. This collapse was based on intentional actions. The Fed sacrificed our purchasing power so that Uncle Sam could afford to overspend wildly through the use of debt.

Here’s the con in four steps:

Gold is the antidote. It’s the anti-dollar. It’s an inflationary hedge. And it’s a fear indicator.

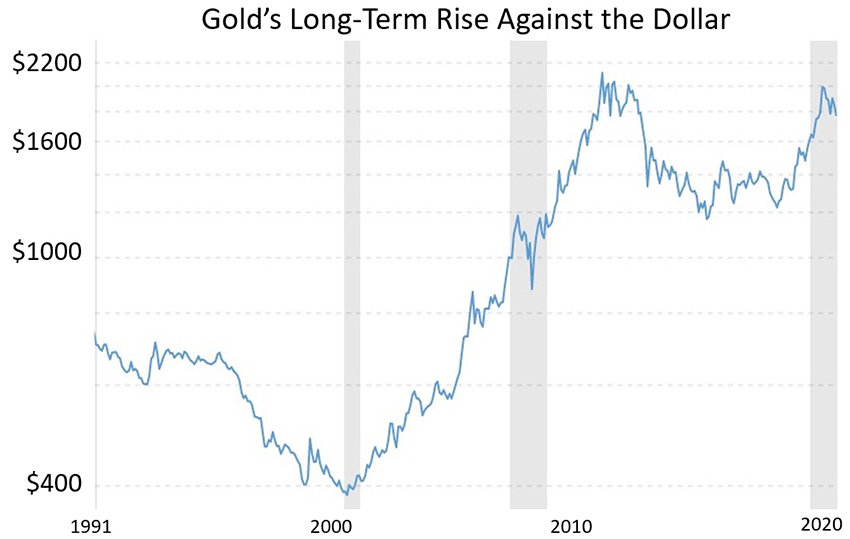

As investors globally grow increasingly worried about the dollar, gold prices rise. You can see that in the chart below. This definitively shows that gold has served as a defense against rising debt and a weakening dollar since 2000, which conveniently squares with the beginning of America’s worsening debt situation and the buck’s slow erosion.

I expect gold will see $2,500 before 2021 calls it quits. Over time, as the dollar continues to drift lower, gold will see higher highs. And with a dollar-debt crisis in our future, gold could see unimagined highs.

This ETF owns all the major miners: Newmont, Barrick Gold, Wheaton Precious Metal, Kinross Gold, etc. They are the big players in the mining industry, the global blue chips. As gold prices rise, they will rise as well because miners have built in leverage that will supercharge your investment.

Their costs—the outlay for building a mine—are largely fixed. As gold prices rise, the value of their

production increases. Aside from some increased tax obligations, all that extra revenue pretty much falls unimpeded to the bottom line.

I like to use this example to show the power of owing gold-mining stocks in a crisis: In the wake of the Great Depression, when FDR confiscated gold and repriced it 69% higher overnight, investors who owned shares of Homestake Mining, the largest miner listed on the New York Stock Exchange at the time, made out like bandits. Homestake’s earnings soared because gold prices were so much higher. Investors saw their investment rise six-fold, as both the share price and the annual dividend payments soared.

IShares MSCI Global Gold Miners ETF is a solid way to own all the top gold miners. As I write this, the shares are trading just under $26. Anything up to $32 will mark a good buying opportunity, given where gold prices—and, thus, this ETF—are headed in a weak-dollar world.

Finally, there’s the Norwegian krone, the currency of Norway.

This is not a safe-haven currency, like the Swissy. Rather, in our current situation, it functions more like gold, given what the Federal Reserve has already announced.

I told you how the Fed manipulates inflation so that government can pay back its debt with cheaper dollars. Well, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has stated that the Fed will not intervene as inflation heats up. The Fed wants inflation to exceed 2% per year.

I fully expect we will see inflation much higher than that. My prediction: At least 4%.

And I might be well under the mark ultimately.

You might know the movie The Big Short—the Hollywood take on the real-life tale of how the U.S. bungled the housing crisis in 2007-08, wiping out trillions of dollars of middle-class wealth in the process. One of the primary players in that saga was Michael Burry, a California hedge fund manager who saw the disaster unfolding two years before the Jenga tower of mortgage stupidity collapsed (he’s played by Christian Bale in the film). No one listened to him. Many of his investors revolted and pulled all their money out of his fund.

Those who remained…they made a combined $700 million when the mortgage industry imploded, just as Burry foresaw. Burry himself took home $100 million.

Why is he important now?

In February he tweeted this:

Prepare for inflation. Pre-COVID it took $3 [in] debt to create $1 [of] GDP, and it is worse now [as Congress preps for another $1.9 billion in stimulus spending].

He then highlighted passages from a book called Dying of Money: Lessons of the Great German and

American Inflations that overlay the hyperinflation of 1920s Germany onto modern America:

Germany [the U.S.] started by not paying adequately for its war [on COVID and the Great Financial Crisis fallout] out of the sacrifices of its people—taxes—but covered its deficits with war loans [Treasuries] and issues of new paper Reichsmarks [dollars]. #doomedtorepeat.

The beneficiaries of inflation are hard assets—commodities such as gold, silver, wheat, soybeans…and oil.

Fiat money such as the dollar has no intrinsic value because it is backed by nothing but faith in government. Commodities always have intrinsic value because a baker can always turn wheat into loaves of bread for customers. A jeweler can always turn gold and silver into wedding bands and whatnot that consumers demand.

Oil had a hideous 2020 thanks to the pandemic. One of the many knock-on effects of that saw oil exploration companies sharply curtail spending on finding new reserves. And here’s the problem with that: Oil demand is ratcheting up again, as evidenced by oil prices having already returned to $60 per barrel.

As demand increases, the world will need new reserves to meet demand. But where will those reserves come from quickly, since exploration companies aren’t spending on finding them?

And what will inflation occurring at the same time mean for oil prices?

My bet: Oil prices sprint past $100 again.

The Norwegian krone’s role in all of this? Well, it’s an oily currency.

Norway is a major global producer of oil, and its currency regularly ebbs and flows with oil prices.

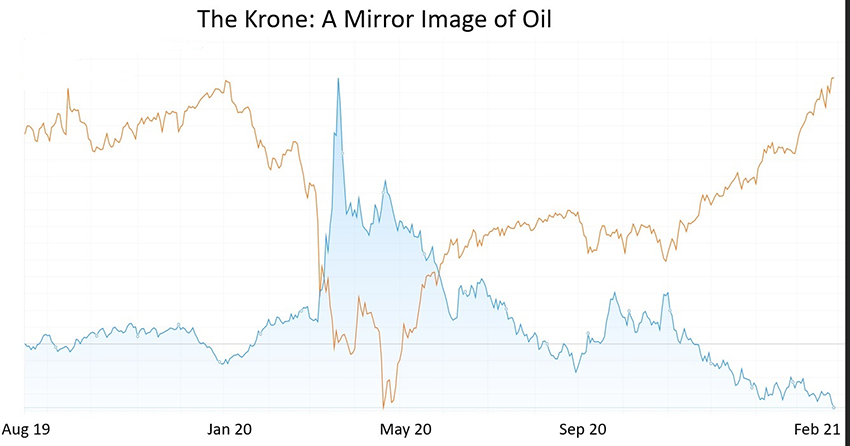

The blue line is the krone-dollar exchange rate. The orange line is oil prices. You can see how the two move pretty much in opposition—meaning the krone buys more dollars (the dollar falls in value) as oil prices rise.

Oil prices, as you see, have been rising; they’re back to $60 per barrel. And the krone…well, there at the peak of that blue spike a dollar bought nearly 12 kroner, while today that same dollar buys less than 9 kroner. Oil is up, the dollar is down relative to the krone.

I want that exposure. It’s an inflation hedge.

There is not a krone ETF, as there is with the Swiss franc. But TIAA Bank offers “Access Accounts” in several currencies, including the krone. You will not earn any interest on this account, and you will have to pay a 0.25% monthly maintenance fee. But as the krone strengthens with rising oil prices rise, that fee won’t mean much.

The other option is to open an account with TransferWise, a global money-transfer service that offers both a website and an app. TransferWise is highly regulated by just about every country it operates in, including the U.S., the U.K., Canada, and various European countries. You can easily convert dollars into more than 50 different currencies—including the krone—and hold them in your account. Again, you won’t receive an interest payment, though neither will you pay a fee.

Either way, you can own krone quite simply and benefit from inflation that sees oil prices rise.

With all these recommendations, you have time to put them in place. It’s not like the dollar will nosedive tomorrow. It’s going to be a slow grind lower. The debt problem is going to mount and mount and mount over time, until there comes a point when something causes the reckoning.

The problems are not going away. Use this opportunity while you have it. Put your protection in place so that your wealth is sheltered from the dollar storm to come.

By Ian Bond

Ian Bond is a banking senior executive with over three decades of experience in wealth and asset management for Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse, and Citigroup. He has built major businesses on four continents and owns online stores that generate millions of dollars in revenue annually.

Imagine if just around the corner from your house, there was a small, well-regarded independent business—a lovingly designed specialty store with an array of carefully chosen products.

The owners have fostered a stellar reputation far beyond your neighborhood. Orders come in from around the country, even overseas. The business has low overheads and it’s profitable. Unlike many small, independently owned businesses, it operates in a booming sector, and sales are growing despite the pandemic (actually, because of it).

The owners, though, are ready to move on. They have other goals and other projects they want to pursue. They want to sell—the premises, the brand, their customer list, everything.

The price: the store’s monthly profit times 30.

At this price, the business is a steal. The price equates to a 40% annual yield, far above the 8% to 10% average annual returns on stocks, or the 2% to 4% on bonds.

Whoever buys the store could have their entire investment paid back in only two-and-a-half years—less if, as seems likely, the business continues to grow. Everything after that is pure profit…an ongoing income that will come in month after month, from a valuable asset that can be sold at any time.

You might imagine that opportunities to buy businesses such as this are rare. In fact, there are countless stores just like this on offer right now through reputable brokers. The only difference is that they aren’t around the corner, they’re online.

Mom-and-pop stores may have disappeared from Main Street, but they’re prospering on the internet. Despite what you may have read in the mainstream media, e-commerce is more than Amazon and eBay. Independent online stores are common, they can be highly profitable, and you can buy them just like you’d buy any other existing business or real estate. (And no, you don’t need a degree in computer programming to own or run them.)

In fact, because of the way these assets are often priced—that roughly 30X monthly profit formula I mentioned—many of these stores are significantly undervalued at present. This situation is temporary, however. Moreover, after decades of ignoring this sector, institutional investors are catching on to its potential and are starting to circle.

But right now, you have a window of opportunity—a chance to purchase your own income-generating online store for less than its true value.

I first learned about this opportunity because of Bear Stearns, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac.

I’ve spent my career working in senior executive positions for major global banks. Ian Bond is a pseudonym. If you knew my real name, you’d find it quoted in The Financial Times, Bloomberg, and elsewhere.

Back in 2007, I was earning a very good living on Wall Street. I was doing some things right—making my 401(k) contributions and taking my stock options—but I had a bloated lifestyle laden with debt. I spent too much and saved too little. I assumed I’d pay off the debt with future raises. Then came the financial crash, and the raises never materialized.

Ageism is a big problem as you near the end of your working life in America. By 2013, I was a 56-year-old short-timer with no big plays left. I was in crisis mode. All I could think about was how to cover the gap between what I needed for my family of five and what I would require for my retirement.

It was clear the solution wouldn’t come from my job, so I sat down and sketched out a retirement income plan. It contained two broad goals: move abroad to extend my career (I now run a banking division in the Middle East), and create an alternate source of retirement income.

My specialty is wealth and asset management. Over the decades, I’ve built wealth management platforms on four continents for some of the world’s leading banks. As such, I’ve studied every investment you can imagine.

So, I took that same skill set and applied it to my personal situation, analyzing dozens of emerging income strategies. That’s how I came across the option of purchasing an online store.

The more I looked into it, the more sense it made. These are revenue-generating assets available at good prices in a sector—e-commerce—that has been trending upward for more than a decade (a trend that has been accelerated by the pandemic).

In 2015, I took the plunge and made an investment in an online specialty store. Only a month later, I bought another. I had zero firsthand experience in e-commerce and little technical know-how, but I was eager to learn.

By 2017, those first two stores were generating more than $2 million in revenue per year. I’ve since added several more stores to my portfolio. For all of these businesses, I pay freelancers to do the majority of the work and I receive a monthly income from each. These businesses saved my retirement.

Most retail investors never move beyond stocks and bonds. Those that do tend to go into real estate. Few even know that it’s possible to purchase a website.

In many ways, however, website investing is like real estate investing, except it’s digital real estate. Virtual or not, these are real businesses with real products and real customers. And the entry price is significantly lower than owning almost any property. Profitable websites are available from as little as $25,000.

The sales formula I mentioned, 30 times monthly profit, is about average in the sector. Websites can go for more or less depending on a number of factors, such as how long the store’s been operating (a big determiner), diversity of sales, diversity of traffic, etc., but it’s generally in the 30 times profit range for younger stores.

What’s key to understand is that the sales figure is calculated not based on the most recent month’s profit, but on the trailing 12 months.

This is why these websites are such an incredible steal right now. Because of the pandemic, we’ve crammed a decade worth of e-commerce adoption into a 10-month period. So, any online store worth its salt has seen its sales grow over the past eight to 10 months.

The data bears this out. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, e-commerce sales grew by almost 37% between the third quarter of 2019 and the third quarter of 2020. That’s an additional $56.3 billion in e-commerce sales in the U.S. alone—over the course of a single calendar year!

I’m among the business owners who’s benefited. The stores I own and operate with my wife had a record year in 2020, with revenues increasing 32% across our eight stores. I expect 2021 sales to be even better. January and February were record months for my stores in nonseasonal categories.

The impact of this is that, for the moment, sales prices are still factoring in several months before e-commerce truly took off in the wake of the pandemic. Imagine a store that recorded $2,000 in monthly profits in March 2020, but had seen 37% growth, so March 2021 profits were $2,740. The sales price of the store would be average profit for the previous 12 months, $2,370 x 30 = $71,100. However, the profits are now $2,740 a month, so you would get back the entire value of your investment in less than 26 months, not 30 months.

The boom in e-commerce is here to stay. U.S. consumers won’t simply forget the advantages of e-commerce. It’s now an engrained behavior. When the pandemic is over, they’ll start traveling again and going back to restaurants, but they won’t resume driving 30 minutes to stand in line at a retail store to get a glass bookcase or fireproof safe.

They’re going to continue ordering specialty items like these online. And not from the big retailers like Target or Amazon, which maybe offer two or three options in these categories. They’ll keep ordering these items from the independent e-commerce websites that specialize in that field and have detailed product info and a variety of options to choose from, like the specialty stores I own.

There’s another reason why now is the perfect moment to invest in an income-generating website: largescale investors haven’t entered this space…yet.

When a new asset class emerges, individual investors always spot the opportunity first. The institutional money comes later, when there is a proven track record of profit. Having worked at major banks on Wall Street for decades, I’ve seen this process repeat time and time again. When I was starting out in the ’80s, this was how it went with junk bonds, international equities, and private equity strategies.

In 2015, when I first started investing in e-commerce websites, there was no institutional capital in the sector. Now that’s changing. Today, a small number of private equity funds are buying websites they can scale using best practices to reap outsized returns—the same thing I’ve been doing with my websites.

Most of these are smaller private equity funds run by wealthy individuals and family offices. Soon, however, this will change. Major endowments and even sovereign wealth funds are now investigating the sector. I expect a public listing of website portfolios by the end of 2022, maybe earlier. But this big money hasn’t fully arrived yet. There is still time to get in first.

To understand how these websites generate income, and why they cost so much less than a standard business or piece of real estate, you need to understand the model they use. This model is called dropshipping.

With dropshipping, your online store acts as the middleman between the customer and the supplier. Your dropshipping store lists and sells the products but you hold zero inventory.

The products are stored at the supplier’s warehouse. When a customer purchases an item from your store, your store generates an order that is automatically sent to the supplier, who then ships the item directly to the customer. It’s hands off for you, other than offering customer service, if there is an issue with the order.

This process is not a modern innovation; it’s been around for generations. This is the same model the QVC shopping channel uses. It’s simply been updated for the digital age.

Because dropshipping stores don’t need warehouses or inventory, they require little capital to operate. The suppliers have to maintain a warehouse and staff; you don’t. In the stores my wife and I run, our only ongoing costs are for some virtual workers, who handle our customer service, and the small fees—less than $150 per month per website—we pay to maintain the stores.

Our customers pay us before we ever place an order with the supplier so we’re never out-of-pocket. We had no bankruptcy risk even during the global pandemic—an enormous advantage for any business owner.

Websites are sold by brokers who independently evaluate the owner’s website before adding it to their listings. But it’s important to note that the brokers represent the owners, not you.

Brokers I’ve worked with include Digital Exits, Empire Flippers, Quiet Light, and FE International. The one I’d recommend for newcomers is Empire Flippers because it is well-established and has a broad selection of sites.

In your online research, you may also come across marketplaces like Flippa and Shopify that have websites for sale at lower prices. Marketplaces are different from brokerages in that they offer sites that may not have been vetted. Generally, the stores on these sites are younger and a riskier buy.

It’s always better to go through a brokerage. The stores will be more expensive, but they will be older, proven sites. That’s what you want to buy.

Also, working with a broker is better than trying to negotiate a private sale because brokers understand the different business models and have a standard evaluation process they apply to each website. They know what a business is selling for in today’s market.

There are several things to look at when you’re evaluating a website. First, I always look for sites selling high-ticket products. Since you don’t have to store inventory or handle shipping, it simply makes sense. It’s easier to get one sale for $5,000 than 100 sales for $50, particularly if you provide the extensive product information that high-ticket buyers expect.

Whatever site you choose, you’ll want to study the business reports prepared by the broker and verify that their initial claims about the website are correct. You’ll be looking at the profit and loss, the breakdown of revenue and expenses, Google Analytics data, and more.

You can also spot growth opportunities during the evaluation process. That growth potential should be a huge factor when deciding to buy.

My strategy: look for a low traffic website that’s still delivering sales. If the owner hasn’t optimized their site with SEO content (specialized blogs and other materials that help a site rank higher on Google), there’s an easy opportunity to increase the traffic and thereby increase your sales. I’ve done this on several of my sites.

Now, I’m not going to lie. That first day you realize you own an income-producing website is equally exhilarating and terrifying. You’re excited for the future of your site, but you don’t want to screw it up. Here are the key steps you’ll want to take in your first 90 days:

Remember, there are no unanswered questions related to evaluating, buying, and running a dropshipping site. There are lots of forums to help you through the process. I blog about it at Professional Website Investors. Brokerages Empire Flippers and Quiet Light also have terrific blogs and podcasts.

Honestly, owning an online store isn’t for everyone. It requires work and there’s a learning curve, but neither is it rocket science. If you think you would enjoy running an old-fashioned mom-and-pop store, then I encourage you to explore this opportunity.

The pandemic has put e-commerce at the forefront of retail, and now is the time to buy in…while website prices remain good and before the private equity funds start throwing their financial muscle around and boosting the value of online real estate.

In my many years traveling the globe, I couldn’t begin to estimate the number of times I’ve sat in an airport lounge or in a café or on a hotel bed and logged into the public WiFi to check my email or my freelance-writing accounts or whatever.

As it turns out, that was pretty unwise…potentially downright dangerous. Or at least, so says the FBI.

In recent years, the bureau has frequently warned about the dangers of using public WiFi. The most recent of these announcements from last October cautioned specifically about the perils of using hotel wireless networks.

The problem with hotel networks—indeed public WiFi in general—is that they are built for convenience, not security, which has made them a preferred target for hackers.

Hotel owners’ primary objective is not to make networks secure, but to stop angry tourists calling the front desk because they can’t figure out how to get YouTube working on little Jimmy’s iPad. This means they often leave their WiFi networks wide open, so anyone can log on whenever they want. Or they have the password written in a prominent public place, or use a basic access system such as a combination of room number and password.

However, if you find it incredibly easy to access the WiFi, so will nefarious actors.

Using these open networks, the FBI advised, could allow hackers to gain access to your browsing history or redirect you to fake log-in pages, where you might input some crucial information, like your company email password, because you believed you were on the official site. With your work email and password, cyberattackers could gain access to your company network and start hoovering up corporate secrets or implant ransomware—a form of malicious software that blocks access to files unless a ransom is paid.

Then there’s the possibility of an “evil twin attack.” This is where the hacker has actually set up the open WiFi network you’re accessing.

I mean, think about it. When we’re looking for public WiFi in a hotel or an airport, we generally just open our phones and click on the one that’s got a correct-sounding name and a strong signal. Thing is, if we log on to a network operated by a hacker, we might as well just hand them over the keys to our digital lives.

The solution, according to the FBI, is to always use a virtual private network, or VPN, on public WiFi.

I first started using a VPN in the mid-2000s. Today, I basically never use the internet without having one turned on…no matter if I’m on public WiFi, on my home internet network, or using 4G on my iPhone.

There are several reasons I always use a VPN when online: First, security and privacy. Even on home WiFi networks, which are generally pretty secure from hackers, VPNs are an effective way to impede Big Brother or Big Zuckerberg or any of the myriad organizations fixated on amassing our personal data.

Second, a VPN is a great way to get access to all sorts of amazing shows and movies and websites that might otherwise be blocked…without spending any extra cash. (This is how I happen to log into to one my favorite streaming services, which I won’t name for fear they read this and flag my account!)

Third, as a digital nomad living and working overseas, I regularly rely on a VPN to access certain financial accounts back in the U.S. because their networks automatically block my Czech-based laptop from logging in.

Now, I know what you’re probably thinking: A virtual private network—it sounds like something that’s going to be impossible to set up or use. The kind of technical jiggery-pokery that’s certain to make your blood boil as soon as you try to install it. And sure enough, when I started using them, that’s exactly what they were like.

When I got my first personal VPN about a dozen or more years ago, it was frankly a nightmare to use. It tended to work on a schedule of its own choosing or slow my internet speeds to a crawl. Sometimes it even froze my laptop, which explains my ill-advised, infrequent use of it on my travels.

Today, however, these services have evolved considerably. The industry leaders are pretty much all reasonably priced, reliable, easy to use, and effective.

Here’s how they work: A VPN basically creates a secure tunnel to a special server located somewhere on the internet.

So, when you connect to a website through a VPN, you first send the data to your VPN server, which then encrypts all the data and connects to the website on your behalf.

Similarly, the data that comes back from the internet passes through the VPN’s server before reaching your computer. So, there is no direct link between your phone or laptop and the internet.

This is why it’s typically safe to use public WiFi with a VPN. Because the data is first encrypted by the VPN, it would be unintelligible to any hacker snooping on the open WiFi.

Now, here’s the really fun thing about VPNs—you can choose the country where the server you connect to is located. Then, because you are connecting through the VPN, the website or streaming service will think you are connecting from that country.

Here’s an example of how you might use this. Imagine you’re in the middle of season one of Twin Peaks on Netflix when you pop over to London on a business trip. Once you get to the hotel, you grab your iPad to continue watching Dale and Harry’s surreal investigation into the murder of beauty queen Laura, only to find that the show has mysteriously disappeared from your Netflix options.

The problem is that Twin Peaks is not available on Netflix in the U.K. This is known as geo-blocking.

Companies, most commonly streaming platforms, limit your choices based on where you are connecting from.

You can get around this, however, by simply opening your VPN, choosing a server in the U.S., and hey presto, you’re back on the U.S. version of Netflix.

The joy of this is, with a good VPN provider, you can connect to a server in pretty much any country. Fan of Asian cinema? Why not check out what’s on offer on Netflix in Japan or Korea?

Like British TV? You could try the BBC iPlayer, a free U.K. streaming platform. Although it’s typically blocked overseas, you can access it with a VPN by connecting through a U.K. server. So, you could watch the best of British TV, like Line of Duty or The Night Manager, for free.

Likewise, you might find that some U.S. websites won’t grant access to you when you’re in the European Union, since they haven’t implemented the EU’s strict General Data Protection Regulations. The image below, for instance, shows what happens when you try to connect to The Baltimore Sun website from the EU. Again, you can circumnavigate these restrictions by connecting through a VPN server in the U.S.

A good VPN will not only seriously improve your entertainment options, it can also restore some of your privacy.

Personal privacy, as we once knew it, is on the verge of extinction. Major global governments are seemingly intent on creating massive digital surveillance states or controlling what their citizens do online, as evidenced by the NSA’s bulk data collection program, the U.K.’s Snooper Charter, and China’s Great Firewall.

Then there’s private industry. The collecting and selling of our personal data is now the biggest business on the planet. As The Economist reported in October, about $1.4 trillion of the combined $1.9 trillion market value of Alphabet (Google’s parent company) and Facebook comes from our data and the firms’ mining of it (once you strip out the value of their assets, cash, and R&D). Even your internet service provider (ISP) is monitoring what you do online and, thanks to Congress,

it can sell anonymized data about you.

If any of this bothers you (and it should), a VPN—with its data encryption capabilities—can provide some level of anonymity. It can’t stop all the ways these firms track you, such as cookies on your browser, but it can shut down a lot of them.

A few pro tips here if you’re looking to circumvent government data collection programs. First, set up your standard VPN connection to a server outside the Fourteen Eyes Alliance—an international intelligence-sharing network spanning the world’s major Western powers, including the U.S., the U.K., and Germany. You can assume that if any of these 14 gets access to your data online, your data can then be shared with the other countries. So choose to access the internet through a VPN in, say, Switzerland.

Second, if you’re planning to visit China, get a VPN before you go. You can’t download one once you’re in China. It’s also technically illegal for individuals to use VPNs in China, though it has been estimated that as many as 30% of China’s web users have one, and there are no reports of foreign nationals being charged for using them.

There are numerous solid choices for VPNs. The best option for you will depend on what you want to use your VPN for and how much you are willing to spend. Here’s my top picks.

Best for streaming: ExpressVPN

ExpressVPN is the VPN I’ve used for the last three or four years on my phone, my laptop, and my TV. I say that not for any personal benefit from the company. I share it because I know the service works well, and I’ve used it all over the world in my travels.

The company provides lightning-fast VPN connections, which is great if you’re going to be regularly streaming shows in high-definition or 4K. It also offers connections through 160 locations around the world. ExpressVPN offers a 30-day free trial, but it’s not the cheapest option on the market. The majority of VPNs are constantly running promotions, so prices can vary from week to week. At time of writing, an annual ExpressVPN subscription was $99.95.

Best for privacy: NordVPN

The biggest name in the industry, Panama-based NordVPN has an independently audited no-log policy, meaning you can be sure they won’t keep any record of what you’re doing online. Plus, it has more server locations than ExpressVPN. At time of writing, NordVPN was running a promotion, offering a discounted one-year plan for $59.

Best bargain: Surfshark

A relatively new entrant on the market, Surfshark has servers in 65 countries. It’s simple to use and unbeatable on price, offering a two-year plan at time of writing for just $59.76. Another advantage of Surfshark is that it offers unlimited devices, meaning you can use the service on as many laptops, desktops, phones, and tablets as you like. (ExpressVPN has a limit of five devices, NordVPN of six.) Ciaran, Global Intelligence’s managing editor, started using Surfshark last November and reports zero problems with connectivity. Given its remarkable price point, this is the best option for most ordinary internet users.

A final thought here is that if you start Googling VPNs, you may come across some free options. Don’t use them. Ever. Running a VPN service is expensive. And just like with Google and Facebook, if the service is free, you are the product. Maybe the free VPN is sticking ads in your browser. Or maybe it’s selling your internet browsing history to the highest bidder so they can serve you targeted ads. Either way, it’s not worth the risk.

OK, so once you’ve handed over your cash, now what? Well, it honestly couldn’t be easier. When you purchase the service, you’ll create your log-in details. Then you’ll be prompted to download the software onto your laptop and log in. For phones/tablets, you get the company’s app in the App Store or Google Play Store.

When making a VPN connection for the first time on your mobile device, the software will need to add VPN configurations. Click “Allow” in the pop-up box on iPhone and “OK” on Android.

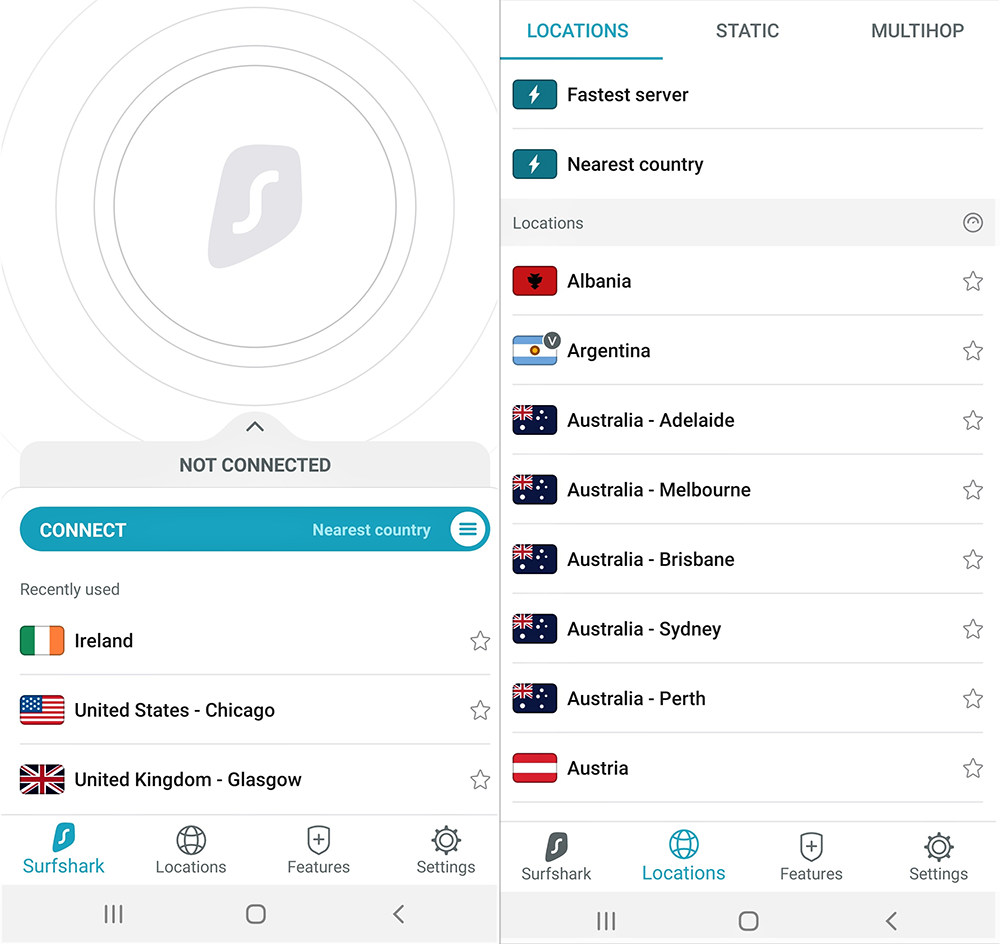

Using these apps is simple. Let’s use the example of Surfshark. This is what the interface looks like:

Once you open the app and log in, you’ll see the home screen (left image), which tells you whether you are currently connected or not. Generally, you’ll just want to connect to the fastest server in your home country or in the nearest country. You can do this by simply clicking on the turquoise connect button.

If you want to change your location to a specific country, you click the location button at the bottom of the screen, which brings up the country list (right image). As you can see, there are generally multiple servers in popular locations such as the U.S. or Australia. So, you’ll always have plenty of options to choose from.

That’s it. Once you’re connected, you’ll see the VPN icon (on iPhone) in the top left-hand corner of your phone so you know it’s turned on. It’s that simple.

As a final note, VPNs do have some practical drawbacks. While VPNs are legal (they’re recommended by the FBI after all), some sites look at VPN traffic as suspicious. So, for instance, it’s possible, though unlikely, you may have to turn it off when logging into your bank.

The bottom line, however, is that the underlying infrastructure of the internet has not been significantly improved in some time, even though most of us now have multiple devices that are vastly more powerful than the best computers 10 or 20 years ago.

That fact, combined with the reality that we’re living more and more of our financial lives online, means it’s prudent to err on the side of caution and take every step possible to protect our digital security. Now, to watch the latest season of Line of Duty on the BBC iPlayer…

In many of the nearly 70 countries I’ve visited, I’ve met expats running successful businesses. Often, these are the kinds of ventures you’d fantasize about owning—bars on Caribbean beaches, cafés in European college towns, scooter rental shops on sun-kissed islands in Greece or Thailand.

I raise this point merely to highlight that the corporate cubicle is far from the only way to earn some scratch; it’s eminently possible to make a living, often a very good living, running an engaging business overseas.

Yes, the world is in a state of flux right now, but in time—before too long I imagine—we’ll all be flying again. So, if you daydream about owning an oceanfront bar or quaint boutique hotel overseas…well, it could be your reality. And here’s the best part: You might not even have to build the business from scratch.

There are websites that show listings of turnkey businesses in incredible destinations overseas, often at prices that may surprise you. Sometimes, when I’ve got a little downtime, I like to scroll through the businesses on these sites, just to imagine what’s possible.

Maybe I’ll pick one up one day. Maybe I won’t. But hey, a bit of escapism never hurt anyone. So, in that spirit, I thought I’d share some of the ones that caught my eye recently.

Now, I obviously haven’t vetted these businesses, so don’t consider these recommendations on any level. Rather they’re a brief window into the possibilities that exist in sunnier climes.

Sailing Tours Business in Greece

When it comes to escapism, few things beat sailing in the glistening waters off Greece. And if you could get paid to do that too…

Well, down in the Aegean Sea, you can pick up a sailing tours company for €110,000 ($133,820), boat included. The business is based on Naxos, in the Cyclades island group. The boat that comes with it is a Beneteau Oceanis 440 from 1995, which the seller claims is in excellent condition.

The company currently provides day tours, multiple days private charters, and sunset sailing trips. It also claims to have annual sales revenue of €85,000 ($103,405) and €15,000 ($18,250) worth of bookings already sold for 2021.

Restaurant and Licensed Bar in France

If you’ve never been able to locate your sea legs, maybe you could try running a little restaurant/bar in Vienne, France.

Located not far from Lyon, Vienne is a laidback riverfront town noted for its Gallo-Roman architecture and spectacular Roman ruins, including a temple and theater, which bring in healthy tourism traffic.

The restaurant/bar has been operating successfully for eight years and is available for just €60,000 ($73,000), since it doesn’t include the premises. Rather you can take over the annual lease of €19,200 ($23,360) for a term of three, six, or nine years. For that price, you also get your living accommodation, since the building comes with three bedrooms, all en suite.

An Ecolodge in Costa Rica

If you’re going to dream, you might as well dream big. So how about picking up and running an ecolodge in tropical Costa Rica?

In the coastal village of Cahuita, near the Costa Rica-Panama border, you can get a 1.2-hectare property with five guest bungalows and an infinity pool for $580,000. Also included are living accommodations for the owner—a four-bedroom, two-bathroom house with a large outdoor kitchen and a wooden terrace.

The existing bungalows have space for 20 guests, and there’s room to add two more buildings on site. The business is also reportedly profitable, with a cash flow of $50,000 or more. To claim your piece of paradise in Costa Rica, check out the listing here.

March has historically been a good month to add bitcoin to your portfolio.

Since I wrote my cover story on bitcoin last month, the crypto rose from just under $34,000 to highs north of $57,000. And then tanked to the mid-$40,000s before moving back up again.

If you were contemplating adding bitcoin to your portfolio, this bull run might have put you off. That’s understandable. I was sure bitcoin would rise in the weeks after the February issue was released, but even I didn’t anticipate this rapid surge. It seems bitcoin’s meteoric ascent since the start of the year—combined with electric car maker Tesla gobbling up $1.5 billion of the currency in February—caused a FOMO (fear of missing out) buying frenzy.

However, if you decided to hold off on investing in bitcoin as the prices skyrocketed, I encourage you to keep a close eye on the crypto in the weeks ahead.

March has historically been bitcoin’s worst performing month. Since 2017, bitcoin has averaged a loss of about 14.7% in March. One possible cause of this is the imminent arrival of tax season, which could be prompting traders to cash out to cover their bills from Uncle Sam.

Ultimately, bitcoin is a highly volatile asset and it’s impossible to say whether the pattern will hold this year, especially given how mainstream the crypto is quickly becoming. But still, it’s worth paying close attention to bitcoin in the month ahead and to act on any significant drops. I’ve acted on the dip below $50,000 that occurred in late-February, and I remain as confident as ever in bitcoin. The number of large bitcoin accounts that are “hodling”—a crypto version of “holding”—is rising. That’s very bullish.

If this company is really preparing for an IPO, then I’m paying attention.

Speaking of Tesla, I think the electric car maker is a seriously overvalued proposition. In fact, I’ve told friends here in Prague that I won’t be surprised if Tesla slumps below $100; it’s about $700 as I write this. The problem is that Tesla just isn’t very good at making cars. (The company got hauled in front of Chinese regulators in February for persistent quality issues with its vehicles.) So, the fact that its market capitalization exceeds the next four or five automakers combined—well, to me that just speaks to the stock market’s irrationality right now.

Still, when it comes to Elon Musk’s other major venture, SpaceX, I have a more positive outlook. In mid-February, SpaceX reportedly completed an equity funding round of $850 million, sending the company’s valuation to about $74 billion. Now, SpaceX is not a publicly traded company, so we can’t invest in it. But what interests me is what some of this funding is for—Starlink.

Starlink is Musk’s crazy ambitious plan to build an internet network using thousands of satellites. Once completed, the system could deliver high-speed internet anywhere on the planet. SpaceX has estimated Starlink will cost north of $10 billion, but might bring in as much as $30 billion a year.

Whether those estimates are true, who knows? But there are already more than 1,000 Starlink satellites in orbit (it’s handy owning your own rocket company) and SpaceX is set to commence a beta—or public test—for subscribers who preordered Starlink for $99 in the U.S., the U.K., and Canada. On top of that, Musk recently reiterated that SpaceX plans to spin off Starlink and take it public. Now, I’m not saying I’m going to invest or anything. It’s much, much too early for that, but I will be watching that public beta closely to see how Starlink performs…

You might want to check if you have any old trading cards in the attic…no, seriously.

Something’s going on with sports collectibles. Maybe it’s all the investors who scored big on bitcoin or GameStop, or just the general boredom of live sports fans due to the pandemic. Whatever the reason, investors are pouring crazy sums into things like trading cards.

How crazy? In early February, a Michael Jordan rookie basketball card in pristine condition sold at auction for a record $738,000. But here’s the thing: The exact same card went for about $215,000 a few weeks before.

One of the reasons for this investment boom appears to be fractional trading. If you haven’t heard of it, fractional trading allows investors to team up to buy a fraction of a share for a company like Amazon, whose share price is near $3,100 at time of writing. Now companies such as Collectable are allowing investors to join forces and speculate on novel assets like trading cards using the same approach.

I’m not sure if this is something I’d personally want to do. Sounds like it might lead to a bubble. But I have thousands of baseball and hockey cards in storage back in the States, all from the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. Many—including a Wayne Gretzky rookie card—are in pristine condition. Maybe I should begin investigating their value. If you have any, I’d advise you to do the same…

Don’t buy something on Amazon before clicking this button.

Before the pandemic, I was an infrequent Amazon shopper. Over the last few months, however, I’ve been relying on Amazon for finding the gear I need to build some crypto mining rigs. So, given the amount of moolah I’ve been handing over to Jeff Bezos of late, I’ve been looking into ways to shop smarter on Amazon.

Here’s one trick I’ve learned: Don’t pay the first price you see. Always check the “Other Sellers on Amazon” button. On more than one occasion, I’ve found another seller offering the exact same product at a much better price. However, if you do find another seller, always doublecheck that they offer the same shipping rates.

This service can help you turn your unwanted gift cards into cash.

Christmas has come and gone, so you might now have a few gift cards gathering dust. Seems like the same thing happens with those gift cards every year. You either forget about them or, like me, you end up with five bucks left on them that you can’t find a way to use.

There is a solution, though—Gift Card Granny. It’s a service that will help you find a company on the web that’s willing to buy your gift card. You just enter the gift card brand and the balance and Gift Card Granny will show you the top offers from gift card websites. The service claims that you can get up to 92% cash back on your unwanted cards.

Alternatively, you can use the platform to trade a card you don’t want for one you do. So, for instance, you might find someone on the platform willing to trade your $100 Jelly- Of-The-Month gift card for their $100 Starbucks card.

How would you like a turnkey house in Italy for less than $10,000?

Now, I know what you’re thinking: “Seriously Jeff, another cheap homes in Italy story?” But hear me out. This one isn’t about one of those €1-home initiatives.

OK, to be fair, the town I want to tell you about, Biccari, in the southeastern region of Puglia, is also selling off dilapidated homes for €1. But those aside, the town is offering turnkey houses for between €7,500 ($9,150) and €13,000 ($15,800). That’s an insane price range. Moreover, Biccari is in a stunning location—surrounded by the Daunia Mountains and only an hour from the coast. All in, this sounds like a much better deal than a €1 fixer-upper.

Details of the homes are set to be posted on the town hall website, or interested parties are invited to contact Biccari’s mayor, Gianfilippo Mignogna, directly through this email.

Should I get a UV phone sanitizer?

Nowadays, there is no item we touch more often than our phones. Amid concerns about hygiene during the pandemic, this has led to significant sales of UV phone sanitizers, which typically take the shape of little wands you wave over your screen, or boxes into which you can insert your phone. But do these devices actually work?

Well, UV-C light in an appropriate dose can neutralize a virus, so yes in a sense, they do work. The broader question, though, is whether they reduce your risk of catching coronavirus in any meaningful way.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said that surfaces are not thought to be a common way the virus actually spreads. Moreover, the common claim that phones are dirtier than other household items, like toilets, is based on half-truths. Yes, our phones have tons of microbes on them, but that doesn’t mean anything in terms of whether you’ll get sick. So, it seems these UV devices are more theater than tool. If you’ve got one, use it. Can’t hurt. But I won’t be rushing out to buy one.

How much money should you keep in your checking account anyway?

Having written several books on personal and family finance, this is one of the questions I get most frequently. Here’s my thinking on the matter: Keep about two months’ worth of living expenses. That’s it.

Far too many people keep an unnecessarily large sum of money in their checking accounts, where it’s likely gathering little or no interest. Instead, keep a healthy amount, enough to cover another few months’ worth of expenses, in a rainy day account that actually offers some interest—say, Marcus by Goldman Sachs High-Yield Online Savings or Synchrony Bank High Yield Savings.

Those online accounts offer 0.5% and 0.6% annual percentage yield, respectively, which is not exactly going to buy you a new condo. But hey, it’s certainly better than what you’re getting with your checking account. And if you feel comfortable in the crypto-sphere, you can turn your physical dollars into a blockchain version called US Dollar Coin (so stable, the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency allows banks to use it for payments) and earn 8.6% to 10% with little risk at BlockFi or Nexo.

Outside of your checking and rainy-day funds, all your other money should be in your retirement and investment accounts, where it can earn you real returns.

Thanks for reading and here’s to living richer.

Jeff D. Opdyke, Editor,

Global Intelligence Letter

© Copyright 2021 by International Living Publishing Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction, copying, or redistribution (electronic or otherwise, including online) is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of International Living, Woodlock House, Carrick Road, Portlaw, Co. Waterford, Ireland. Global Intelligence Letter is published monthly. Copies of this e-newsletter are furnished directly by subscription only. Annual subscription is $149. To place an order or make an inquiry, visit www.internationalliving.com/about-il/customer-service. Global Intelligence Letter presents information and research believed to be reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. There may be dangers associated with international travel and investment, and readers should investigate any opportunity fully before committing to it. Nothing in this e-newsletter should be considered personalized advice, and no communication by our employees to you should be deemed as personalized financial or investment advice, or personalized advice of any kind. We expressly forbid our writers from having a financial interest in any security they personally recommend to readers. All of our employees and agents must wait 24 hours after online publication prior to following an initial recommendation. Any investments recommended in this letter should be made only after consulting with your investment adviser and only after reviewing the prospectus or financial statements of the company.