Does Divorcing Uncle Sam Make Financial Sense?

Every quarter, the U.S. government publishes a list of citizens and green card holders who have legally given up their citizenship or long-term resident status.

This list of so-called “covered expatriates” only lists people who (a) had over $2 million in worldwide assets, (b) paid an average annual federal income tax of at least $190,000 over the previous five years, or (c) were non-compliant with any U.S. tax obligations for the five years before expatriation.

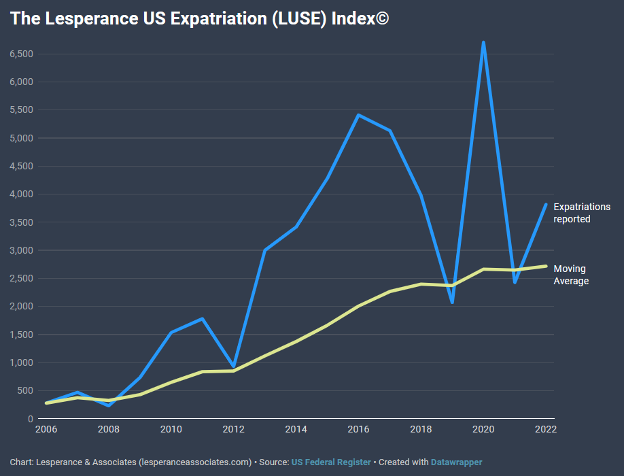

There were 286 covered expatriates in 2006. Fourteen years later, there were nearly 7,000. The yearly average over the period was 2,717, but that excludes two years in which the State Department’s shutdown of consular services due to COVID made it impossible to complete the process.

Despite that, the moving average is clear:

The State Department doesn’t provide any information that could help explain why this number is rising. More importantly, it doesn’t report on the voluntary expatriates who didn’t fall under those wealth and income categories.

The reason for that is… money.

You need to pay a range of complex and painful penalties to give up your U.S. citizenship or green card. But the expatriation penalties only apply to covered expatriates. That’s where the big money is—at least as far as the IRS is concerned.

Expatriation penalties fall under the Exit Tax and the Inheritance Tax.

The defining feature of the Exit Tax is that the worldwide net assets of a potential expatriate are treated as if they were sold on the day before citizenship or resident status is terminated. An exclusion of $821,000 is applied to the resulting theoretical capital gain. The remaining capital gain is taxed at the expatriate’s final U.S. tax bracket.

The Exit Tax also imposes an accelerated drawdown regime on things like IRAs, pensions, deferred compensation, and interest in U.S. trusts. Retirement plans and health savings accounts are deemed to be fully distributed on the day before expatriation. However, early distribution penalties don’t apply.

Deferred compensation arrangements and other sources of ongoing income in the U.S. are taxed at a 30% flat rate, withheld by the plan administrator. All foreign pensions or deferred compensation plans are deemed distributed fully at expatriation.

The Inheritance Tax also imposes a 40% tax liability on U.S. citizens or permanent residents who receive a gift or bequest from a covered expatriate. This is to prevent potential expatriates from shifting their fortunes to relatives or friends to avoid the Exit Tax.

So, as you can see, giving up your U.S. citizenship can be a very costly endeavor.

That’s why, for most Americans, giving up U.S. citizenship is not the best way to eliminate your tax burden to Uncle Sam. (I’ll be sharing more advisable, legal strategies for reducing or eliminating your taxes to the IRS at a special online seminar on April 27 called How to Pay Zero Taxes. Details here.)

For now, I want to reflect on why thousands of U.S. residents are willing to go through this rigamarole to end their relationship to the country.

The heavy exit and inheritance tax penalties on expatriates are a result of the U.S. citizenship-based tax system.

Americans are taxed based on citizenship rather than location. (By contrast, citizens of other countries can simply inform the government that they have moved abroad and give up their tax resident status.)

In other words, U.S. tax obligations are like original sin: They are inherent in the individual and remain in place until officially excised.

The only way to do that is through formal renunciation.

Any American who wishes to live, work, or invest in another country is free to do so. There are even significant tax advantages to moving overseas. It follows, then, that there are only two compelling reasons for voluntary expatriation.

First, for whatever reason, a citizen develops enough of a dislike for their country that they no longer wish to be part of it. We can safely assume that although such people surely exist, their numbers are likely quite small.

The second possible motivation is to permanently end U.S. tax status. This is almost certainly the case for most people who have expatriated in the last 15 years or so.

Do these people dislike the amount of tax they must pay to the U.S., or do they disapprove of what that money is being spent on? There’s no way to know.

The only thing that is 100% certain is that for better or worse, the IRS and the Congress who writes its rules are absolutely right: expatriation is about tax avoidance. And maybe, for some very wealthy individuals, that makes sense.

Whether that justifies the draconian penalties imposed on people who choose this path is another question entirely.

Not signed up to Jeff’s Field Notes?

Sign up for FREE by entering your email in the box below and you’ll get his latest insights and analysis delivered direct to your inbox every day (you can unsubscribe at any time). Plus, when you sign up now, you’ll receive a FREE report and bonus video on how to get a second passport. Simply enter your email below to get started.