Why the Real Inflation Crisis Started Decades Ago

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about inflation… specifically the price increases almost nobody talks about.

Inflation is a powerful psychological issue. When the prices of daily necessities rise rapidly, people become upset. That makes inflation a prime target for political manipulation and disinformation.

When an issue like inflation is politicized, it’s easy to make bad decisions.

That’s why you need to know the truth about inflation. And the reality is that the most damaging form of inflation isn’t the newly elevated cost of meat and eggs in the grocery aisle.

Rather, it’s decades-old “hidden inflation” in categories essential to our development and survival.

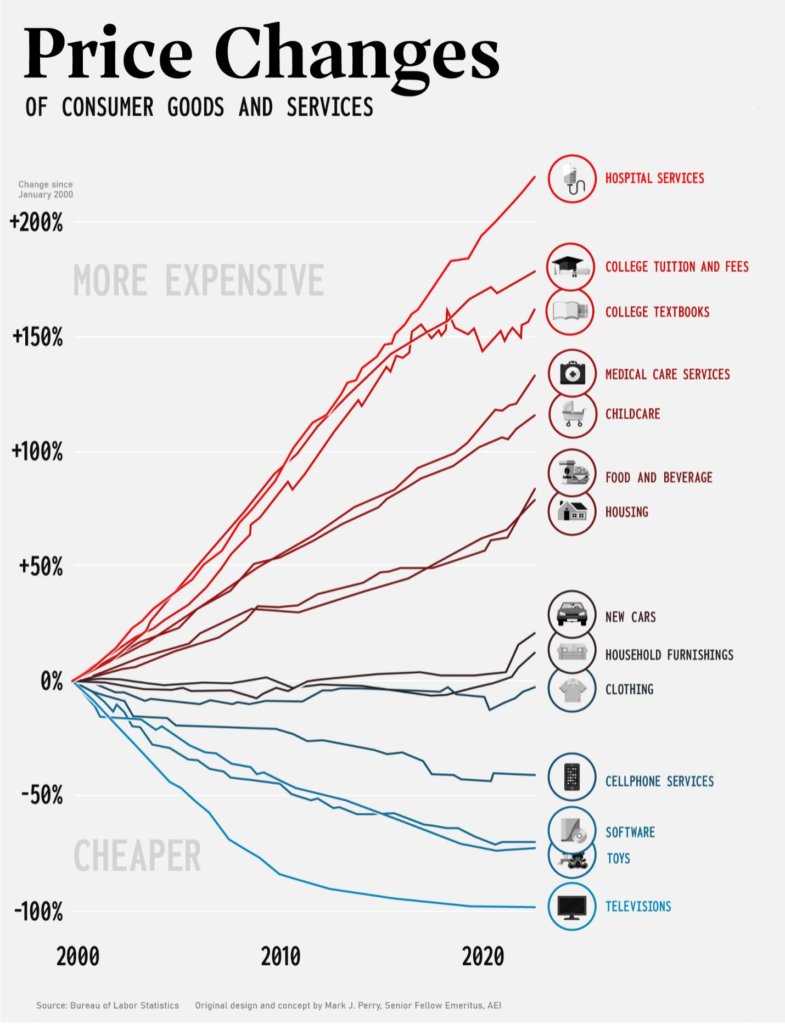

You can see this in the chart below, which shows the relative change in prices for various U.S. goods and services over the past two decades:

The industries with the biggest price increases deal in “non-tradables”—things that can only be produced in the same economy where they’re consumed.

By contrast, the sectors with big price declines are traded globally, especially with China.

The long-term increase in non-tradable goods far outweigh the recent uptick in consumer goods. So why didn’t people get upset about that? Here’s what I think:

- They don’t notice them. People whose kids don’t go to college aren’t aware of the crippling increase in tuition costs and might not care even if they knew. The same is true of childcare costs in communities with extended families, where relatives can look after the kids.

- Sometimes they benefited. Increases in residential property values over the last two decades have made some households very well off (even if others got burned).

- Someone else is paying. The U.S. employer-based health insurance system obscures the enormous increase in medical costs. As cost have risen, insurers have raised their premiums. Employers have absorbed those costs by keeping take home pay stagnant. The situation with Medicare is similar.

- There’s no political advantage to calling attention to it. It’s true that some politicians have complained about medical and education costs for years, but the first three issues make it difficult to get any traction.

Like the frog in slowly heating water, these background price increases haven’t had the same psychological impact as recent inflation. That makes them hard to politicize. But that doesn’t mean they haven’t played a role.

With the costs of healthcare, education and childcare skyrocketing, real wages have stagnated for decades. People managed as long as consumer goods prices were falling thanks to China. But post-COVID inflation has hit exactly those kinds of imported products (including inputs to food production, like energy and fertilizers). With little spare income thanks to “hidden” long-term price hikes in other areas, the recent spike in prices of everyday goods has had a huge psychological impact.

That makes the “new inflation” ripe for political manipulation. I hear a lot of people saying they want to leave the U.S. because of it. I get that. But a better reason is the nature of “old inflation.”

Healthcare and education costs haven’t risen between 150% and 200% in the last 20 years for economic reasons. The causes are political.

Take healthcare, for example. U.S. medicine prices are about three times higher than in peer countries. Former Louisiana congressman Billy Tauzin has a lot to do with that.

In 2003, he chaired the congressional committee that refused to allow the government to negotiate drug prices for Medicare. The next year, he took over as the CEO of the main lobbying organization for the U.S. pharmaceutical industry, where he collected a $10 million salary for the next decade.

Hospitals are another pressure point. In the last 20 years, private equity firms have aggressively consolidated hospital and physician groups into regional monopolies that can set their own prices. In many parts of the country there is effectively only one healthcare provider. Despite numerous investigations showing how damaging this trend is, the government has declined to act.

On the education front, the National Center for Education Statistics reports that in the early ’60s, the average cost of in-state tuition was $250 at a public four-year university, and a little over $1,000 at private institutions. If costs had remained in line with inflation, annual fees today would be around $2,000 and $8,500, respectively.

Instead, the average public university charges over $9,000 a year, while private universities charge nearly $33,000. But the real money is in housing: some colleges charge over $70,000 a year for a dorm room.

The reason is the steady decline in state-level funding for public universities.

Since public institutions now rely primarily on individual tuition charges, they have an incentive to try to appeal to upper middle class and affluent families who pay full tuition. That means larding college campuses with fancy facilities designed to attract such households. The result is an arms race between universities for such facilities, leading to spiraling costs.

There’s also been an explosion in the number of non-academic staff to deal with issues that used to be handled at home, like healthcare and counseling. Over the last 25 years, the number of university administrators has risen twice as fast as the number of students.

Meanwhile, student loan debt is nearing $2 trillion, with the average graduate owing more than $35,000.

In both cases, political choices have had a direct impact on “hidden inflation.” Because these political choices are often the result of lobbying by the industries concerned, politicians have an incentive not to talk about them, or to deflect blame to other issues. As Upton Sinclair once said, “it’s hard to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

Politicians have the opposite incentive when it comes to everyday consumer prices. Those price increases hurt a lot more than they would if people weren’t already paying far more than citizens in comparable countries for core needs like healthcare and education.

But you won’t hear politicians saying that. So yes, inflation is an incentive to look for a home in a foreign country. But an even bigger reason is the political dysfunction that makes that inflation so painful in the first place.

Not signed up to Jeff’s Field Notes?

Sign up for FREE by entering your email in the box below and you’ll get his latest insights and analysis delivered direct to your inbox every day (you can unsubscribe at any time). Plus, when you sign up now, you’ll receive a FREE report and bonus video on how to get a second passport. Simply enter your email below to get started.