Insights That Could Save You $1,000s…

Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

It’s the sort of question you get asked at a high school graduation or maybe a college admissions interview.

Those of us further in life probably haven’t been asked it in a long, long time…

But I ask exactly this question when I take on new clients who are ready to diversify globally. You see, if you’re going to make the most of all the opportunities available to you overseas—to save on taxes, protect your wealth, make profitable investments, and simply live better—then you need to envision what that ideal life looks like, before I help you work out the steps to get there.

There’s no reason those of us closer to retirement age—or already there—shouldn’t dream big for the years ahead… just like high school or college students.

And the possibilities for a better and wealthier life overseas take so many forms.

Recently, I helped an International Living reader cut her tax obligations in half…

Debbie approached me about getting a residency visa in Europe. Her son was already a resident of this particular country, and married to a local. She was also considering buying a property for herself there with the proceeds from her US home.

I helped her clarify the visa categories for which she’d be eligible, plus the tax implications of various ways to do the property transaction. With this advice, she’ll likely cut her potential tax obligations in half, if not more. This is exactly how I help readers like you all the time.

In my personal consultation clinics, there are topics that come up again and again, whether it’s tax considerations, the best ways to own property overseas, or the right visa categories to consider.

So I thought I’d share the answers to some of these questions. Maybe you’ve been wondering the same things…

1. How do I make enough passive income to qualify for a visa in country X?

Retirement visas are the most popular goal for many of my readers. They’re more often called “independent means” or “nonlucrative” visas. The main requirement is that you have enough passive income to be able to support yourself, which is usually set at a specific multiple of that country’s minimum wage. The income can come from pensions, dividends, interest, rental income, annuities, or any other source that doesn’t come from current work.

On paper, the required amounts are reasonable. Portugal, for example, will give you a D7 retirement visa if you earn about €1,300 a month. Other countries are more expensive, anywhere from €2,500 to €3,500. But these are minimums. Most countries give their immigration officials discretion to decide how much to ask from an applicant to issue the visa. When lots of people are applying, as in Portugal, they’re far quicker to issue the permit to people who are well off than to those on the borderline. And if you have health issues or any other problems that suggest you might end up relying on the state for support, they’ll turn you down flat if you don’t bring in a lot of money.

This is why it’s so important to start thinking about your finances well before you decide to make an offshore move. Many people come to me assuming their Social Security income will be enough, but if it’s close to the cutoff point, you may struggle to get the visa.

If you’re seriously thinking about moving to another country on a passive income visa, my advice is to supplement your anticipated pension and Social Security income with investments in dividend-generating assets. These include things like stocks, municipal bonds, mutual funds, closed-end funds, and other financial instruments that pay a percentage of the value of your investment on a regular basis.

For example, $200,000 invested in assets that yield 7% a year, paid monthly, will give you a monthly dividend income of a little over $1,150 before taxes. Added to your Social Security income, that could be enough to push you closer to the top of the pile when it comes to applying for a retirement visa. Of course, it’s not always easy to put that kind of money together… especially if you’re already retired. That leads to the next most common question.

2. How much time do I have to spend in a country to keep a visa?

This is an issue with hidden financial implications. Most countries consider you a tax resident after 183 days of living there during a tax year. If you get a D7 visa in Portugal, you’ll have to pay Portuguese taxes after you’ve been there six months.

That’s why countries like Portugal require you to be present for at least 183 days to maintain the validity of your visa. The point of inviting people to come and spend their retirement or other income is to boost the economy. That includes taxing expats. And in countries where you’re eligible for the national healthcare system as part of your visa, you’ve got to pay your way like everyone else.

The one exception to time-in-country requirements: Golden Visas—i.e., visas based on an investment. Most countries ask that you only be there a week or two a year in order to maintain the visa. What they really want is that big investment, so even if you’re not there to spend money, they’re still happy with the deal.

A similar approach applies to some countries’ advanced skills visas, which allow you long-term residency without having to be in the country, as long as you contribute expertise to the local economy.

3. Will I have to pay tax in the country I’m planning to live in? If so, won’t that make it unaffordable?

There are a few countries that don’t tax foreign-source income, i.e., income generated from outside its borders. Costa Rica and Panama, for example, don’t tax pensions or other income you bring in from outside.

Most countries in Europe, on the other hand, have higher tax rates than the US, and you’ll pay on your foreign-source income. (There are some exceptions, like Montenegro, where the tax rates max out at 15%.) If you were to move to Portugal, you’d be looking at a maximum tax rate of 43% on income that might attract a tax burden of 20% to 25% in the US.

But in most cases, you won’t pay tax twice on the same dollar of income. Many countries have double taxation treaties with the US so that IRS taxes on distributions from your retirement accounts are deducted from your foreign tax bill. The only thing you’ll pay to the foreign country is the difference between your payments to the IRS and what you owe the former.

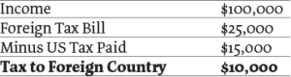

Let’s say you have income of $100,000, and you’ve paid 15% ($15,000) to the IRS. Your foreign-country tax bill arrives and you owe 25% on your $100,000 income. But you’ll get credit for what you’ve already paid to the IRS—so you’ll actually only owe $10,000 to the foreign country, not $25,000. Here’s an illustration:

If you live in a country with higher tax rates than the US, you’ll pay more taxes overall than if you stayed in the US. That’s why I advise people to understand what might offset your foreign tax obligations.

For example, many people who live in southern Europe say that they spend less overall than they would in the US, even though they’re paying higher taxes. That’s because the cost of living is far lower, and you get things like healthcare almost free.

These are the kind of questions I help people grapple with before they hit “send” on a visa application.

The last time I heard from Debbie, her plans were progressing nicely, with her US house up for sale, and her foreign visa application in the works. She’d deferred purchasing a foreign home until she had spent a couple of years there to make sure she found just the right place.

Not signed up to Jeff’s Field Notes?

Sign up for FREE by entering your email in the box below and you’ll get his latest insights and analysis delivered direct to your inbox every day (you can unsubscribe at any time). Plus, when you sign up now, you’ll receive a FREE report and bonus video on how to get a second passport. Simply enter your email below to get started.